Hi out there —

I’m teaching a workshop next week at the majestic Zapata Ranch, and while I gear up for that, I should mention two upcoming workshops that are now open for registration:

October 31 to November 17, 2023: “From Memory to Story,” an online class on writing personal narrative; Tuesdays and Fridays, 9:00-11:00 Pacific.

January 15 to 19, 2024: “Writing to Restore,” an in-person writing-based creative retreat at Tanque Verde Ranch in Tucson. This is a new offering, and I’m very, very excited about it.

In case you need a nudge, here’s what two students from a recent online class said about the experience:

I can't say enough about how valuable this class was for me. You are a gifted and passionate instructor. I felt privileged to listen (and see) you and my classmates every week — and I will miss the weekly routine also. You lit the fire. — Ken B.

Your class was wonderful and [I] so appreciated the kind and honest way you work with people. Everything we did in the short amount of time was so encouraging and really ignited things. Thank you! — NS

I love my job(s). Now, getting down to business —

On the morning of Tuesday, May 23, I took Gilbert for a walk and decided to use the time to call my friend Ben in Memphis. Back in January, we’d made a casual pact to pick up the phone and call anytime we thought of it, even and especially if we had only a few minutes to spare, a quick interlude between meetings or en route to somewhere— carpe diem, we said, but with a lower bar, like carpe eight minutes. Ben had kept up his end of the agreement, calling a half-dozen times between January and mid-May, each time leaving a voicemail replete with good feeling. Even in the best of times, I am bad at answering the phone, and having a baby in the house has made me even worse. It was my turn, way past my turn. So I put on my sneakers, grabbed Gilbert’s leash, and picked up the phone.

Ben never says hello. Margaret! He booms. Ben is one of only two people on Earth who’ve called me by my legal name, and the other one is deceased. Margaret, he repeated, drawing out the syllables. How are you?

There is little conversational foreplay in a phone call with Ben. We get right to it. I was alright, I told him. Ames had just turned four months old. Ash was back at work. Ames now had a part-time nanny, the same part-time nanny we had when June was a baby, which felt like, and in fact is, a miracle. But if we’d talked a couple of months earlier, I told him, times were bleak. Ben is married but has no children, so I indulged myself and spared no detail.

With a newborn, I explained, weeks eight to 11 are purgatory. The baby doesn’t yet sleep well at night, but the benevolent tidal wave of new-baby glee and offers of support from loved ones have ebbed to an occasional splash, and the buoy of elation that hefted you through the early weeks slips loose and begins a slow drift out to sea, and there you still are, now dog-paddling (mostly) alone, or alone with your baby’s other parent, trying to remember the deadman float you learned in childhood swim lessons, and meanwhile the sleep debt continues to accumulate, garbling your thinking, though because it’s your thinking that is garbled, you’re not able to see that your thinking is garbled. Every few days, whenever we had a moment of lucidity, I’d turn to Ash, or they’d turn to me, and one of us would raise a fist limply in the air and intone the mantra we’d coined in mid-2020: SURVIVAL, NOT THRIVE-AL!

But that was two months ago, I reiterated. We’re alright now, solidly alright. Where we are now feels sustainable, and that means more than it sounds like.

So like that, we were off. Ben told me that he’d broken his arm in February. Though it was fine now, the cascading repercussions of it — physical, medical, relational — had shaken him. Ben said he’d come away from the experience with a kind of altered perspective on his everyday life. And to keep cultivating that perspective, he’d taken up a journaling practice. It’s been very clarifying, he said.

This kind of introspection is something I expect from Ben. It’s a foundational aspect of our friendship: the honest self-appraisal, the exchange of introspections. But when he said “journaling practice,” I felt weird. I felt weird because I was envious.

I have never kept a journal or diary. Sometimes, when immersed in a book project, I’ve done a stint of morning pages à la Julia Cameron. It’s helpful, but I never stick with it for more than a couple of weeks. My reasons for stopping won’t surprise anyone: a lack of time, a lack of discipline, the little satan in my brain who reminds me that I have ‘real’ work, etc. Some of the reasons are dumber than that: my hand cramps when I write longhand, and it can be tiring just thinking my thoughts, much less writing them down. Here’s what I think it’s really about: I’m a tiny bit of an exhibitionist, and writing is only fun for me when there’s a chance someone else will read it. (I don’t count as someone.) For all of these reasons, I made peace years ago with not being a journal-keeper — except when someone I admire tells me about their devotion to journaling. Then I am not at peace. Edan Lepucki, I am thinking of you. And Ben.

The thing is, despite my having let myself off the journaling hook a while back, I have never stopped wanting to be someone who wanted to journal. Whenever I am teaching, someone asks me to describe my writing practice, and specifically, do I write every day? The first few years of fielding this question, I gave fumbling non-answers, because I have never had a writing ‘practice.’ I have written when I had a deadline. Sometimes the deadline was self-imposed, and sometimes it is set by an editor. Either way, I don’t wake up itching to write, and I could go (and have gone) days and months and years without writing a thing. For a long time I was fairly certain this meant I was doing a bad job of being a writer. I was falling behind, though I also wasn’t exactly sure what I was behind at. But everyone who has ever taken a writing class, or read a book about writing, or attended an author reading — everyone can tell you the rules: to be a good writer, you must write every day.

It’s not like I can argue with that. To be a good writer, it is very helpful to write every day. It’s a goal to aim for, albeit reductive and kind of scold-y. Now I’m being defensive, but the admonishment to write every day sounds a lot like saying that unless you can afford to be an art monster — the kind of solitary and obsessive (and typically male) creator who lives only for the work — you don’t get to succeed at your art. Yes, some writers do write every day. But many of us write sporadically, for a host of reasons. Does the work improve faster if you write more regularly? Probably. Sure. But being a writer is like anything else: there’s got to be more than one way to do it.

I have never written every day, not in the 16 years that I have made a (partial) living from writing. Even when I am actively working on a book, I do not write every day. I have other work to do, paid and unpaid — plus, just, life. Most people, especially women, do more than one type of work. I also, just — I enjoy doing things that aren’t writing. Writing is difficult and time-consuming. I don’t feel incomplete if I don’t write — though by some paradoxical logic, I do feel more complete if I do? Writing is not for me an instinct or an impulse, but something more like a refrain: I return to it again and again, because that’s the way the song moves forward.

Writing is a necessary act, but it is not a constant one. For me and many other women writers especially, the act of writing is “provisional, contingent, subject to disruption — and yet the words are still coming and the work is getting done,” writes Julie Phillips in The Baby on the Fire Escape. In a chapter about Ursula K. Le Guin, Phillips paraphrases “The Fisherwoman’s Daughter,” a lecture by Le Guin on writers who are mothers:

What must remain within the writer’s control, [Le Guin] concludes, is not the time or the place, but her writing self, for the duration of the time available. A writer doesn’t have to have a room of her own or the goodwill of a partner, though they both help. What she needs is a pencil, paper, and the knowledge “that she and she alone is in charge of that pencil, and responsible . . . for what it writes on the paper. In other words, that she’s free. Not wholly free. Never wholly free. Maybe very partially. Maybe only in this one act, this sitting for a snatched moment being a woman writing, fishing the mind’s lake.”

The point of this mighty tangent is, any time spent writing counts. Any amount written is something. It is more words than the writer would have if she hadn’t written. The words add up; they accumulate; eventually, they constitute a body of work. It’s like taking a walk: any distance you go is more than you would have covered if you’d stayed home. That the writing may be fitful doesn’t undermine the work’s progress, its value, or its promise.

Last week one of my students, a woman who has been writing assiduously for more than three years (that I know of), confessed that she doesn’t feel she can call herself a writer. She works full-time and is a married mother of two, and she has nonetheless managed to write tens of thousands of words in the off-hours. She has not yet published, though she hopes to. But she is a writer by my accounting — and not only because she is writing, but because writing is a necessary part of how she understands herself. It doesn’t matter to me if she ever publishes, though I want it for her because she wants it. Only an infinitesimal number of writers will ever be published anyway, and publishing doesn’t make you more of a writer. It just makes you a published writer.

A person becomes a writer by caring enough to keep at it. It is a feat of persistence and an act of perpetual self-authorization. A writer is a person who engages with words and sentences as a way of being in the world. But that engagement doesn’t always have to look like writing. It can also look like reading, listening, noticing.

I know I am touchy about this, but I am tired of tilting at this windmill, the lingering sense that I’m doing it wrong. When Ben mentioned his journaling practice, I felt mildly wounded. And though Ben’s journaling has nothing to do with me and even less to do with some crusty old notion that writers have to write every day or else — that’s where my brain went, at least for a minute. Because, fuck it, I do still want to know what it’s like to be someone who writes every day, despite all I’ve said in the preceding paragraphs. I was jealous of my friend.

I decided to tell Ben what was on my mind, because we have a grown-up friendship, and I try to be a grownup in it. He admitted that, before this practice, he’d never stuck with journaling either. Hearing this, I felt slightly better. I even felt a little happy for him. And then, because being mature felt kind of refreshing, I thought: Well, what if I continue being mature? What if I try journaling???????

I asked Ben to tell me about his method. It’s a five-minute practice consisting of six prompts, he said, and he does it every morning. Apparently you’re supposed to do some of the prompts in the morning and some in the evening, but Ben is an animal who cannot be tamed, and he does the whole thing in the morning. I asked him to text me the prompts.

Here they are, in the order in which they should be tackled:

GREAT MOMENTS YESTERDAY (3 things)

YESTERDAY I LEARNED (3)

I AM GRATEFUL FOR (3)

WHAT WOULD MAKE TODAY GREAT (3)

I AFFIRM (2)

I MIGHT FEEL BETTER IF (2)

The prompts come from a book called The Five Minute Journal, which boasts that it uses “proven principles of positive psychology.” (And alliteration!) Ben tweaked the prompts’ language a bit to his liking, and having now looked up the book myself, I prefer Ben’s wording. For instance, where Ben’s prompt reads simply, “I affirm,” the book asks you to write “daily affirmations,” two words forever linked in my psyche to the Codependent No More desk calendar my mother kept atop her dresser in the early nineties. Also, Stuart Smalley.

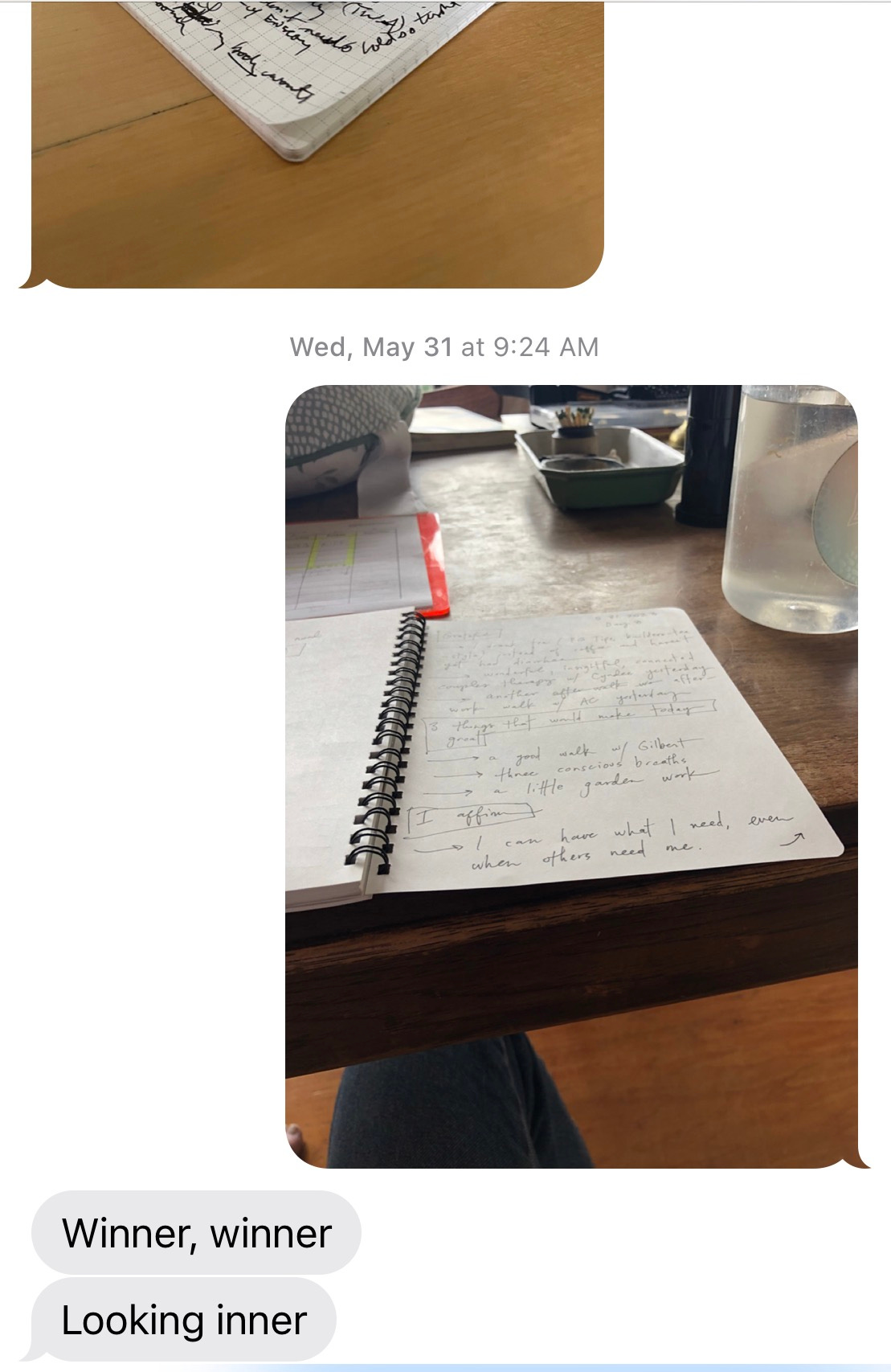

I wrote down Ben’s prompts in a notebook, and I put the notebook on the kitchen table. By the end of lunch on the same day, I had completed my first journal entry. It took little more than the promised five minutes, and I felt deliriously accomplished afterward. That felt good! I texted Ben. He replied with a photo of himself on a hiking trail in some desert locale, facing the camera with his fist raised, mouth open wide, and head thrown back, either cheering my triumph or being stung by a cactus.

He next morning, he texted again: Would you like to do a 30-day journaling challenge w/ me? I wrote back before I could overthink it: Yes, I would! We agreed to text each day after doing our journal, just a single word like “done” or “complete.”

Instead, without planning it, we began sending a photo each day of our journal entry, sometimes legible and sometimes not. I am nosy, so every time Ben’s photo arrives, I zoom in, poking at the screen, trying to decipher his handwriting. Each day I write my journal with the hope that he’s reading mine too, because of course I do. It has the pleasantly counterintuitive effect of making me more honest. A week in, he rewarded my efforts with a rhyme.

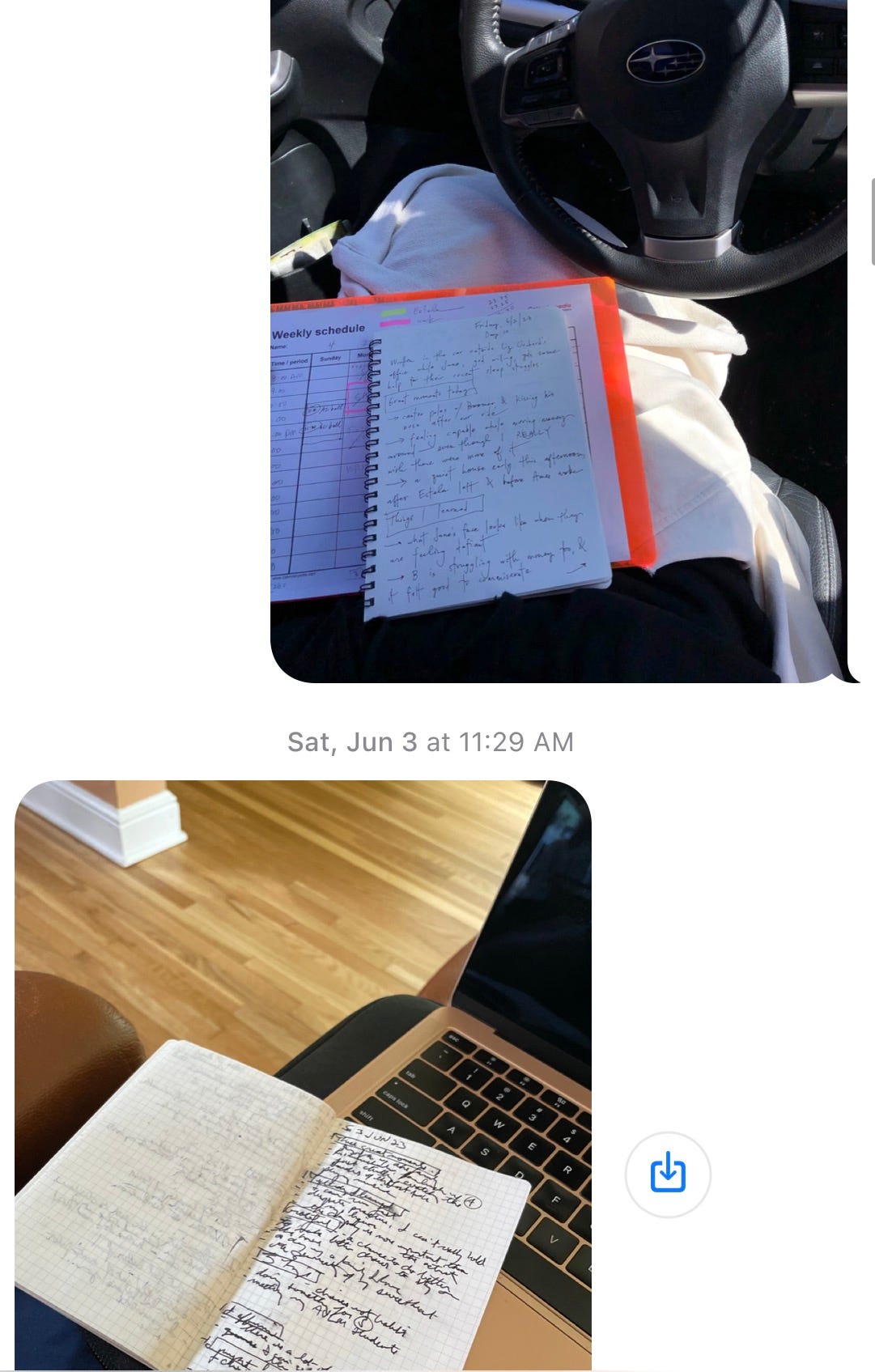

I have journaled at the kitchen table, at my desk, on the kitchen counter, in the car, and in a church pew while waiting for a community theater production to start. I aim to journal in the morning, before anything else; if not then, over lunch; if not then, sometime before bed. I write it on my to-do list for each day, so I get the thrill of crossing it off. I have journaled happily and journaled like it’s a chore. I have journaled my remorse, and I have journaled my pride. I have journaled about inducing vomiting in Gilbert when we thought he had swallowed an AirPod, and how I had to rush him out of the house for a walk so he wouldn’t make a mess inside, but I had to bring the baby too and the stroller and a mug of tea and the pumpkin muffin I’d been eating, because I was very hungry, and what a vision we were, and how I began, by celestial intervention, to laugh instead of sob as I dragging us all up the street, shoving the stroller with my hip, the dog repeatedly heaving and my milky tea sloshing and me cramming the muffin in my mouth with the hand that wasn’t holding the leash. (Gilbert was fine.)

As of today, June 21, Ben and I are on day 29. We have each missed one day, according to my records. The words accumulate anyway. Just shy of three weeks in, I filled a notebook that I’d been trudging through since last November.

I think what I like best about this practice is that it doesn’t ask a lot. You’re making lists. It doesn’t even require complete sentences — though once I begin, I usually feel my mind’s tongue, or whatever, loosen up, and I wind up saying more than I’d expected. I start to enjoy making sentences, because I can. And while the prompts don’t require me to write at length, they do make me reflect, guiding me to be clear, realistic, and — best of all — specific.

The phrasing of the prompts is nuanced, even more so the longer I work with them. For example, take “what would make today great” and “I might feel better if”: they sound similar, -ish, but the first, as I read it, invites me to set near-term goals, even daydream a little. In contrast, the second nudges me to focus on how I feel, what’s weighing on me, and what might help. For the former, I might write, “1:1 time with June,” or “stay flexible about afternoon plans”; for the latter, it could be “finish that infernal essay about journaling,” “take a shower,” “go to bed early,” “take a shower,” or “take a shower.” Strangely, when I reflect in the morning on the fact that I might feel better if I take a shower that day, I wind up showering. Is this why people journal? It’s a wild ride.

Last week, when I started writing this essay, I envisioned the point being something about my having stumbled not so much into writing every day, but into an alternate way of being awake to the world as a writer. What I was thinking was: surely journaling this way isn’t “real” writing. I intended to offer a bloodless and semi-apologetic conclusion, something like, My journal may just be a list and not legitimate writing, but yay, it’s a way of staying in communication with my writer’s mind. But now that I’ve made it to the penultimate paragraph of the aforementioned infernal essay, I’ve decided that’s a lie. This practice is more than that, means more than that. It turns out, hey-o, that this is an essay about how I found a way to write every day for 29 days, or pfffft, 28 — and to even enjoy it. This is the essay in which, for a month and counting, I become a journal-keeper! Let the record show! I did it on my terms. Ben’s terms. Terms.

Yesterday I told Ben that I intend to keep going past our thirty-day goal. He does too. I think we are both elated — by the accountability, the regular contact, the way the writing reverberates down the length of each day. I don’t know how long I’ll stay with it. I mean, I might stop. I might get bored with it. I will absolutely stop. But when I do, I can begin again anytime, as often as I want. At the end of a given day’s page, I will always have more than I started with.

“I can begin again anytime, as often as I want.” !!!! This is about the most affirming and empowering thing I can imagine reading and oh! Thank you for writing it. (And thanks for sharing this connection you retain with Ben, about whom those of us who have been reading for a long time have, I think, some fondness). I have struggled with journaling for.ever. And this made me feel interested and even excited to try.

Love and relate so, so much. As a fellow never-been-fully-committed journaler, thank you for the glimpse into your process -- and the babaà reference made me giggle out loud.