"It’s either going to sound like the minutes from a business meeting, or like pornography"

Or, a conversation with Catherine Newman

When I started this newsletter, I wanted to make space for other voices to join me here. Every now and then, I’ll share with you a conversation with someone whose work and mind I admire. Today, we are lucky enough to hang out with the writer Catherine Newman, whose new kids’ book What Can I Say? comes out on May 24.

The conversation below — which took place on April 22, on Zoom — says pretty much everything I might have hoped to write in an introduction, so let’s just dive into it. Please enjoy! FYI: most of the book-related links are affiliate links to Bookshop.org, which supports independent bookstores. What follows has been edited for clarity, and to minimize our nonsense. And to Catherine: thank you.

Molly Wizenberg: Hello!

Catherine Newman: Hiiiiiiiii!

MW: I loved that you emailed me earlier to confirm that we were still meeting today, so you’d know if you needed to shower or not. I really struggle to motivate to shower. I’m always glad I’ve done it, but, like, it takes up time.

CN: I know, and there’s that moment when you get out and you’re cold, which I don’t like, and I’m wet, and it offends the cats when I have wet hair. I think it’s a pandemic thing. My dad – he turns ninety one week from today – he was just saying, and you have to picture the heavy New York Jewish accent: Yeah, since the pandemic, I’ve started changing my underpants every other day. And I was like, [laughing] Okay! I mean, it’s fiiiiiiiiine.

MW: So, you’ve got a new book, a kids’ book, coming out on May 24. And then your first adult novel, We All Want Impossible Things, will be out in November.

CN: Yes, “adult novel” – which always makes it sound like an X-rated book. I like to say that, adult novel. I like to work it into conversation.

MW: I think my first introduction to you was Waiting for Birdy. Someone recommended your book to me when I was pregnant. It was one of two or three narrative accounts of young motherhood that I read during that period, and I’m not going to say what the other one was, because I didn’t like it as much as yours. I loved Waiting for Birdy. I was charmed, and I hope this isn’t weird, but I sort of aspired to strike the chord as a parent that I saw you striking in that book, which a very, like, polyphonic chord. It was in no way a record of ‘perfect’ parenthood, but here was a loving family, a playful family, quick to laugh, intuitive, nerdy, informed without being anxious or hovering, all these things. Did you always know you wanted to be a parent?

CN: Ah, what an interesting question.

MW: Is that too personal?

CN: Me? You could ask me literally anything and I would answer. Yes, I always wanted to be a parent. It’s funny how you get older and then you’re like, Oh, I am very particularly of the people who raised me, in ways you can’t see until then. It’s only occurring to me now. So, my dad is a New York Jew – Eastern European, grew up in Montreal first, then in New York in this house full of, like, loud-talking, argumentative, really funny Jews. My mother is from England. She’s 85 and has this incredibly cute British accent still. And she can, like, you know, cold you out like nobody else. I mean, she’s so warm as a parent, but she’s very crisp-speaking and has a real sense of what is and isn’t appropriate. And lately I’m like, Oh my god, I’m so a product of these two people. I write an etiquette column, but I’m incredibly crass in real life.

MW: It’s perfect. I love that you’re somebody who writes books like How to Be A Person or What Can I Say?, and yet you do it in a way that’s irreverent.

CN: That’s my hope.

MW: Growing up the child of these two parents, did you have a particular vision for what adult life was supposed to look like?

CN: Oh my god. Yes. I mean, so much. And I’m so not living any part of it. I mean, the obvious things are missing, like quicksand. [Laughs.]

MW: We all thought there was going to be SO much quicksand.

CN: And we all knew how to get out of it, and to never come back, and all that. But no, um, I always assumed that there would come a point where I would need to wear pantyhose. I’m starting to think that is really never gonna happen. But it’s weird. It’s like I hold a space for these, these adult things that I always assumed would happen. But maybe I’m never going to wear pantyhose. That’s exciting to me. . . . My mom was and is gorgeous. She was a stay-at-home mom. She picked me up from school. She made all her own clothes with, like, Chanel patterns and, oh my god, a hand-cranked sewing machine that she’d brought from England. In her trunk, on a boat. I mean, just crazy. So here was my mom, picking me up from school with her hair in a chignon and then a silk scarf tied under her chin. She wore perfume. She smelled good. She was gorgeous and put together. And I guess I assumed I would become that, and, oh my god, I have never been that. The first time I put mascara on, my kids said, There’s something on your eyelashes, Mom. There’s something gross on your eyelashes. You should probably get it off. I have none of that – you know, moving through the world in that graceful way. But I always assumed it would come, like I hadn’t grown into it yet. I pictured it. But alas, no, not to be. Did you picture something that never happened – or that did happen?

MW: My mom was and is gorgeous, like your mom. She had all the designer clothes. I always thought she was just so beautiful, and it seemed to me that she always did things the right way. My family was very loving and progressive, but there were a lot of aspects of their adult life that I just never questioned. I naturally fell close to the tree, and that suited me. It never occurred to me as a kid that I could crawl a little farther away if I wanted to and still be okay.

CN: And then you did crawl a little farther away.

MW: I did. And the cool thing has been, like – so now my mom lives in Seattle, a block from me, and she’s 75, and I don’t think she would mind me saying this, but I feel like she’s chilled out a lot. I like seeing her in a place where there is literally no use for all those old designer blouses. [Laughs.] She’s out there, still changing in her seventies, doing interesting things, making a bunch of interesting friends. That’s inspiring to see.

CN: I love that. It’s true. Both my parents – but my dad, I’ve walked in on my dad asking Birdy, my daughter, about what it means to be trans, and what is ‘cis,’ and he’s there scooping up hummus. He’s so not the same person who raised me, in so many ways. It’s incredible to watch your parents and the way love expands them. Birdy is gay. She’s kind of butch. And they love her so passionately that they just expand their worldview to include her, and they’ll expand it as far as they need to. I feel it so deeply. I’m making myself cry.

MW: That’s gorgeous.

CN: I know, right?

MW: I have another question about when you were younger. You have a PhD, right?

CN: I do, I do! I have a PhD in Literature and Women’s Studies from UC Santa Cruz. I got it in the nineties, wearing my Queer Nation stickers all over everything, and being in an open relationship with the person who is now my husband, and my girlfriend would pick me up on her motorcycle outside my feminist theory class. Oh man, it was the whole nineties, this whole nineties —

MW: Wait a minute. You and your husband started out in an open relationship?

CN: Well, we didn’t start out in one, but we evolved into one, because we were so young when we met. I was 21. He was 21, 22. We’re the same age. We met in college, and then we moved to San Francisco. And I was queer and, like, not into monogamy. I had a lot of stuff going on. We thought, Well, we’ll try to stay together through this, which, in hindsight, I don’t recommend. It’s a real setup, especially if really only one person feels that way and the other person is sort of along for the ride. He consented to it and was a mensch about it, to be clear, but it was not the greatest. I’m sure there are people who do it well. We did not do it super well. But we stayed together.

MW: Brandon and I, as you know, had a period when our relationship was open, to accommodate my shifting sexuality.

CN: I know!

MW: And we did it very poorly. It’s not something I expect to do again. I mean, never say never, but no.

CN: I know what you mean. But you did it in good faith. You didn’t know. You were coming through something and didn’t know what the other side was going to look like. That was true for me too. Turns out, I did want to be with Michael. But I also did need to do some stuff in my twenties. I was such a kid. And I was really selfish, just to be honest, but that’s a whole other story.

MW: Maybe we’ll have to talk again when your adult novel comes out.

CN: [Laughs.] There is some sex in my novel, which my daughter Birdy read, and she loved it. The best character in the novel is very closely based on her. I was writing it during the pandemic, and Birdy is just the funniest person to live with. It’s just nonstop her saying crazy, really funny things. And the novel is filled with that unfolding in real life – Birdy coming in and saying some ridiculous thing. And then Ben, my older child, is like, I don’t really want to read about Mama having sex. Because there IS some sex in it. And Birdy was like, Well, it’s fiction, Ben. It’s just fiction. It’s not about Mama having sex. But it kind of secretly is.

MW: While we’re talking a bit about your husband, he’s a massage therapist, right?

CN: Yes. Who also has a PhD that he doesn’t use.

MW: All my favorite people have graduate degrees they don’t use.

CN: He has a PhD from Berkeley! A philosophy PhD from Berkeley. And the thing is, that was not his thing. He is the most outrageously talented massage therapist. He was a terrible academic. I mean, he was good enough to get a PhD, but the passion? He didn’t have it.

MW: You know, I'm interested in how little you write about him.

CN: [Laughs.]

MW: I wondered if you would talk about that a bit.

CN: [Still laughing.] I know what you mean. I don’t write about him that much.

MW: I want to clarify that it’s not that I expect you to, but I follow you on Instagram and I’ve read your work for years, and you write often about everyday life and domesticity, and I know you’re married to sort of a hunk. He seems to be a really good one. So I wonder how you negotiate that territory — what you write, and what you don’t.

CN: It’s strange. He’s weirdly in the novel the most, as a fictionalized version of himself. Because in a weird way, that’s where he is the most plausible. He’s so, he is such an incredible mensch that I always feel like it’s going to be alienating to read about him. I worry.

MW: That he seems too good?

CN: He’s an incredible caretaker and sweetheart and… and, you know, emotionally distant – it’s not like he’s this perfect guy, far from it. But when the kids were little and I was writing, he was such a hands-on parent and so great with the kids and babies that I felt self-conscious. I didn’t do it on purpose, but that’s what I think it maybe was. I also feel protective of him. And then there’s this weird way – I mean, you’re still in a new relationship, so maybe you don’t feel like this – but I feel like if I write about us, not fictionally, it’s either going to sound like the minutes from a business meeting, or like pornography. [Laughing to the point of wheezing.] There’s nothing just, like, regular and interesting.

MW: This answer is everything I ever needed.

CN: We’re, like, running this business, which is our home. I mean, we’re empty-nesting now, which is a whole other thing. But when the kids were home, you know all the cliches are true. Every morning, you’re like, Who’s gonna blah blah blah – it’s like running a business, even though it’s just your family. And then it’s also really private and, you know, dirty. And we fight. And I haven’t really written about that, except fictionally a bit.

MW: You’re negotiating that tricky space of writing about your own life while being an actual person.

CN: Yeah, I think some of that. Ultimately, I’ve only really ever written about myself. It might have seemed like I was writing about the kids, but I’ve never actually written about their subjective lives and experiences. I’ve only really written about myself as a parent. I think that’s why Michael is not so much in it. It’s like I’m just writing about this experience of myself parenting, not even so much about being in a family.

MW: I'm really glad you said that, because it’s something that not a lot of people notice about personal narrative writing. I get a lot of questions about how other people have felt when they’ve appeared in my writing. Which is fair, and important to talk about. But by and large, there's so much less about other people in my work than there is about myself.

CN: Exactly. Even when it seems like it's about other people, it’s your subjective experience.

MW: That’s the only way to do it well. On a different note, you work at Amherst, right?

CN: Yes, I'm the academic department coordinator of creative writing, which is basically like a secretary job. It's a half time job with benefits and summers off. So we’re two freelance people, with a benefits job. Actually, last spring, I was director of creative writing and also the department secretary, which I thought was so my life come to its full fruition that I could hardly stand it. I was my own secretary, basically, which is exactly how I feel about myself. I wrote my own performance review. It was the best.

MW: I thought you were gonna say it was the worst because you were doing the work of two people! But I love that this is your perspective on it.

CN: [Laughing.] It was just so classic for me. Anyway, I’ve been there for twenty years.

MW: Well, I’m amazed. I know that for someone to produce as much writing as you do, you clearly work really hard at it. And you’ve managed to do that while still having another job that is actually meaningful. Do you write every day? How do you get it done? Because you get it done.

CN: I write a lot on deadline. I do a lot of magazine work. I mean, I’m still writing for money, I’d like to say, so that’s great, because there are built-in deadlines. You just have to get it done, and I love that. I’m not waiting to be inspired. I just have to turn it in, or I don’t get paid. So that I love, and that’s an important part of my writing practice. I used to always wish I didn’t have to do stuff for money, but now, oh my god, if I didn’t have to do stuff for money… [laughing]. I wouldn’t write at all. I am so motivated by having to write.

It’s all accountability. I have used every type of accountability thing. I have a friend, KJ Dell’Antonia, and I was trying to write a kids’ novel maybe five years ago, and she and I had this accountability group. It was just the two of us, and you had to produce 500 words of discretionary writing a week, which meant writing that was not assigned, not for actual deadlines. It meant writing your pet project, which for me was this novel. We checked in on Friday at five, and if you didn’t do it, you had to make a donation to Donald Trump’s campaign. And neither of us ever didn’t do our writing. And it was 500 words a week. As a writer, that’s not a lot.

MW: What I love about it is, well, when I’m in a book project and it is my full-time job – which has been maybe four years of my life, in total – sure, yeah, I can produce 1000 words a day. I can produce more than that, even. But that’s a special case. Most of my working life doesn’t look like that. I can’t be a normal person in the world and earn actual money and write 1000 words a day. So 500 words a week? I love it.

CN: And you could obviously write more, if you wanted. Anyway, that was an excellent accountability project. And my other one, during the pandemic, when I was writing my adult novel…. I have to stop saying it in that way.

MW: No, no, keep saying it.

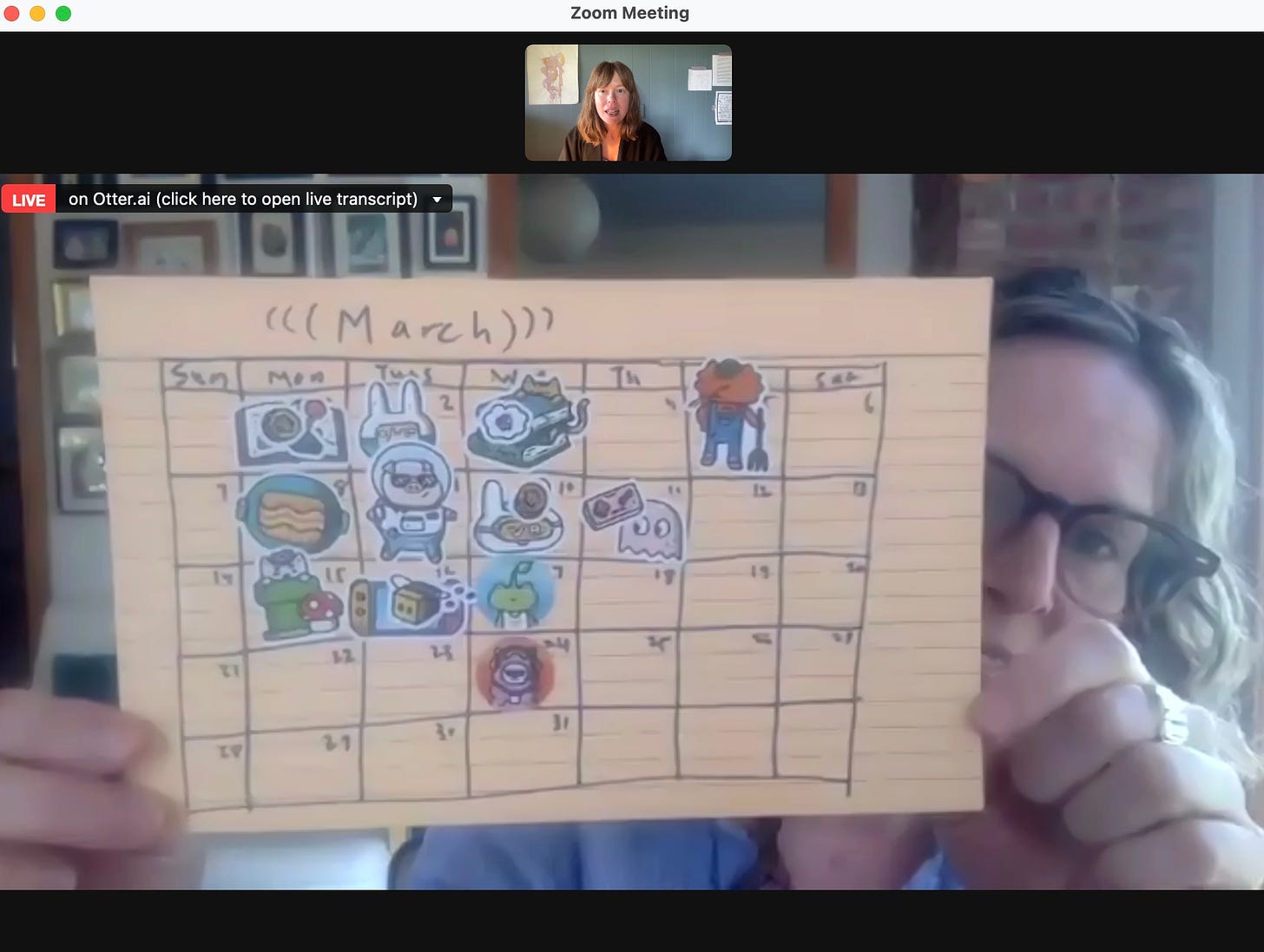

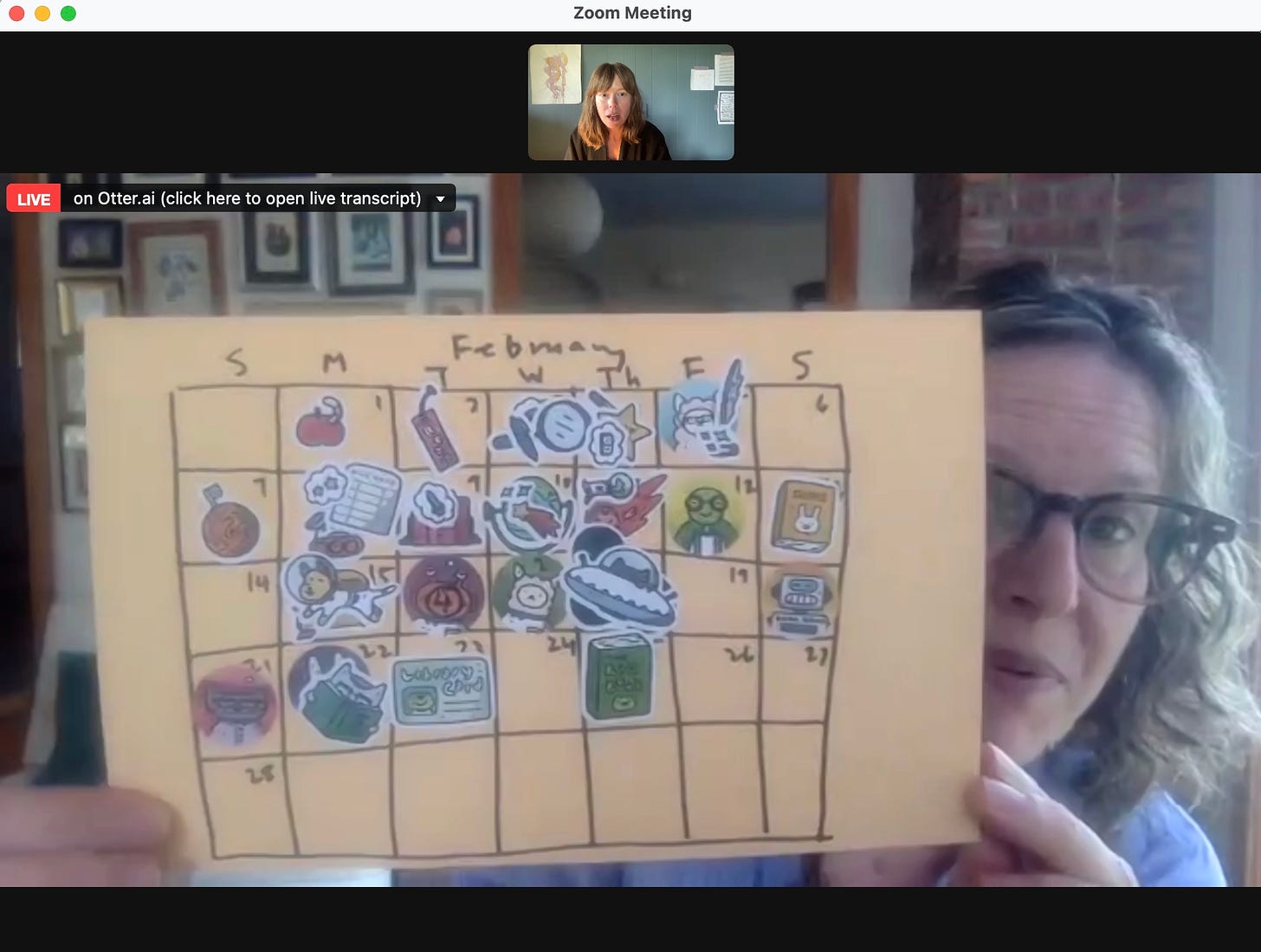

CN: Adult novel. Well, this is based on a writing group that I’m part of on Facebook called #amwriting where people always showed their sticker charts. I’m embarrassed to say this. I made myself a sticker chart. I should go get it. I just hand-wrote a grid of the month. Wait one second. Do you mind?

[Catherine disappears for about thirty seconds, and I hear some thumping from another room, and then she comes back, laughing to herself.]

CN: Molly, this is so ridiculous.

MW: Oh, bring it on.

CN: So, this is the month of March. I got a sticker every time I wrote 500 words.

MW: And did you give yourself the sticker?

CN: I gave myself a sticker.

MW: So you were like the department chair and the secretary.

CN: [Scream-laughs.] Thank you for that. Exactly. I was my own interlocutor. I bought the stickers. I gave them to myself. Is it not just the most precious, ridiculous thing? Can you stand it? I had to write 500 words to get a sticker, and it worked so well, it was embarrassing to me, to be the person who wanted to have written enough to give myself a sticker that I picked out and bought and put on my own sticker chart. This is February.

MW: So it was 500 words per day?

CN: I got a sticker whenever I wrote 500 words. So if I wrote 350 words and then the day ended, I was reset to zero the next day.

MW: Got it.

CN: It was incredible to me. I would write 850 words, and I’d be like, Damn it, I’m just gonna get one sticker for that. So I’d write another 150 words. I shit you not. This is the kind of person I turn out to be. I will actually keep my butt in the chair for a little longer so I can give myself another sticker. My children, as I’m sure you imagine – they were both home because of Covid – and they were heartbroken by it they were both home because of COVID. They were heartbroken by it. They were like, Oh god, Mama, your sticker chart. It’s so sad.

MW: Some days are just papered in stickers. Multiple stickers.

CN: I had not ever had that experience, to be honest. People used to talk about it and it drove me crazy. It sounded very out there, when people talk about channeling their characters. I was always like, just doing the work. But I really got into it. It’s quite autobiographical, this novel. My best friend died about seven years ago, in hospice, and the book takes place in hospice. The narrator’s best friend is dying in hospice. It was like a love letter that was pouring out of me – which makes it sound so dull, I know, but it was an incredible experience to get to write it.

MW: I can't wait to read it. Speaking of books, let’s talk about What Can I Say?. I bought my daughter a copy of How to Be a Person, and I think I sent you a picture of her reading it, unprompted. She loved it. They’re intended to be companion books, right? How did they come about?

CN: The story I tell about it is a true story. Birdy is the kind of person who, if she feels like you’re going to start explaining something to her, she loses her mind. She gets so irritated. She does not want to be explained to. Now she’s a teenager who is exactly like that still. At some point, I was like, Hey, Grandma and Grandpa are coming. Can you sweep the kitchen floor for me, please? And she said, I'm happy to do that. I don't know how to, and I don't want you to talk to me about it. And I was like, You're impossible and annoying, and I don't know how this is gonna happen. But because of that experience, I went to the library and said, Give me your book that’s, like, a huge photo-illustrated guide to chores, for kids. Can I check that out? And they were like, That’s not a thing. So I pitched my publisher the great big chores book for kids. This is literally what it was called: The Great Big Chores Book for Kids. I wanted it to be this thick [holds her fingers apart], and I wanted each chore to be accompanied by a multi-step photo essay with tons of closeups: the dustpan braced on the floor, the little strip of dust after you sweep it into the pan, the hand cupped under the counter that the crumbs are going into. I will continue to insist that this book should exist. My publisher was like, That's the least fun idea we've ever been pitched.

But over time, we changed it enough that now it’s just a lot of skills, but I still think of the chores. That’s the heart of the book. That said, because we expanded into other kinds of skills, we got to get in communication skills, which, if I have an area of expertise, that is it. I think a lot about communication. I’ve taught both my kids to write a killer email, and they thank me for that. I swear to god, once a week, my kids – who are both in college now – will be like, Thank you for teaching me to write an email.

MW: Which is detailed in How to Be a Person.

CN: And then What Can I Say? is that part of How to Be a Person, blown open. We got a ton of feedback from kids – which is the pleasure of writing a book for children, that they send you handwritten thank-you notes, and videos of themselves making quesadillas; I got like fifty videos of kids making quesadillas, which I treasure – but a lot of kids were like, I wish there were more about, like, how to talk awkwardly to your grandma, and other very specific social questions. Small talk came up a bunch, which is a life skill like any other. So we decided to treat all of those social skills as teachable, learnable life skills, rather than these mysterious things you're just supposed to absorb from the air. How do you make small talk? How do you introduce yourself? How do you sit next to somebody on a bus? How do you be an ally, and how do you argue with somebody, and how do you interrupt bullying? There’s some stuff about dating, and not dating, and stuff about gender and nonbinary kids.

MW: Something that meant a lot to me was the section on how to be supportive when someone confides in you. That's a skill that many – so many adults – aren't good at.

CN: When my daughter was a teenager and going through really difficult emotions, I remember learning to just say, Are you needing to vent, or do you want help figuring this out? Because it’s not always clear. Maybe they just want to say it, and they want you to say, Oh my god, that suuuuuuucks, or What an asshole, or wrap your arms around them.

MW: The first thing you say in that section is that if someone confides in you, you should feel honored by their trust. That’s so true. We don’t often think that way. We get busy panicking, wondering what to say. But that little detail really can slow us down, maybe help us remember the relationship here, so we get in a better position to respond well and with real presence.

CN: Slowing down. It’s funny that you should say that, because that is still my lesson. I’m 53, and there are still things I’m so actively working on. Being reactive is one of them. So remembering, like, take a breath!

MW: So you can respond in a way that isn’t about you, the receiver. A way that stays in the relationship.

CN: Not to be overly deep, but I’ve always thought, raising Ben and Birdy, you’re human and you’re a parent, and you do a million things wrong. We’ve apologized. It’s all fine. But what we’ve always hoped is that we don’t leave them with these really deep holes that other people need to shovel into for their whole lives. You know when you meet people who have such deep holes – and you’re in it, you’ll shovel for a while, or forever, depending on your commitment to that person. But it’s so much work, and it asks so much. I think about that, and I want to not give my children these giant emotional holes. Because when someone doesn’t have [a giant emotional hole] and you share things with them, they don’t need to take what you’ve shared and stuff it into their hole. Like, if you share information with someone and they don’t respond the way you hope, that’s someone who’s taking the information and trying to stuff it into their hole. But if they don’t have a big deep hole, they don’t need to do that.

MW: They can stay with you instead.

CN: Not that we don’t all have holes, but…

MW: No, we’ll all wind up with holes, but hopefully our holes are small, and hopefully we know where they are, you know?

CN: That! Even just that – that you know where your holes are.

MW: Yeah, yeah. Oh, this is the best.

CN: I knew it was gonna be fun.

MW: Anything else? Anything you wanted to talk about that we didn’t get to?

CN: I will say that I just reread The Knockout Queen, by Rufi Thorpe. Have you read it? I thought you might ask me about what I’m reading, so I planned to say that. It’s so incredibly good. I don’t have time to reread books. I almost never do it. But I read it cover to cover in a day. I’m recommending it to your [newsletter] people, but I’m really recommending it to you.

MW: I can’t wait. Thank you.

CN: This was so much fun. It was so nice. Thank you.

MW: And don’t worry – I’ll edit this down and make us both sound, um, very well-spoken.

CN: Good luck!

I love it when my favorite writers connect, and I get to read about it. Such a treat!

MW: All my favorite people have graduate degrees they don’t use.

I've never felt so seen.