I had a weird experience a couple of weeks ago, skimming my email inbox. I get a number of email digests from the New York Times, and October 8th’s “Opinion Today” had a particularly clickbait-y subject line: “The secret that divorced mothers know.” I bit, or clicked, whatever, and quickly skimmed the opening paragraph. It was a teaser for an op-ed essay by writer Amy Shearn, titled “A 50/50 Custody Arrangement Could Save Your Marriage.” Shearn’s email begins:

If you were a parent during the worst of the pandemic — and probably even if you weren’t — you know that American parents have it hard these days, and that mothers have it almost impossible. But I’m guessing some people might be surprised to hear that mothers who are partnered actually do more housework and child care than mothers who are divorced.1 The research bears this out — or you could just ask any divorced mother who has 50/50 custody, and she’ll probably confirm it.

I had to read that paragraph three times before I could figure out what was supposed to be surprising about the phrase in bold. Now five years divorced from my ex-husband, I forgot that it had once been a revelation to me, the sheer amount of time I gained when we separated. Much of that newly freed-up time had previously been occupied with parenting our daughter, of course; now, with her at her dad’s for half of each week, those hours were suddenly mine. But it was more than that. Though I continued to live in the same house that we had shared as a family, with the same amount of rooms to keep up with, there was vastly less housework to do once I was the only adult living there. The difference was stark, like flipping a switch. I became a better parent, too, in the wake of my separation: more patient, more playful, less quick to anger, all-around better-resourced.

I wrote about this some in The Fixed Stars, the way in which time expanded after I was separated and then divorced. If we’re to oversimplify things for the purposes of illustration, let’s say that, in my marriage, my ex-husband had represented one unit of domestic work, and our child another one unit. Divorced, with 50/50 custody, I had reduced my care-load by 75%.2

So about Shearn’s NYT op-ed: yes, yes, emphatically yes!, married (or otherwise partnered) mothers do more domestic labor than divorced mothers with shared custody. (Those last three words are absolutely crucial, I should note: not all divorced parents share custody. I cannot speak to the experience of a divorced mother with primary or sole custody. Socioeconomics and class also play a huge role. I do not know what it’s like to be a divorced mother struggling to make enough money to support herself and her child(ren). If the previous sentences describe you, I’d be grateful to hear your take on this in the comments. Thank you in advance.)

What I’m trying to say is, Shearn’s op-ed points to a basic fact that I had to get divorced(!) in order to learn. It’s a fact that changed my life as a woman, something that I cannot and would never wish to unlearn: it is eminently reasonable to expect my partner-slash-co-parent to do an equal share of the tasks required to sustain our family. Maybe the rest of you figured this out long before I did? I hope so, but I also bet not.

Of course, it’s complicated, because gender is involved. Not all married and/or partnered mothers do more domestic labor than their divorced and co-parenting counterparts. Studies show that this imbalance is more common in heterosexual marriages than in queer ones, Shearn notes. I highly doubt anyone reading this newsletter is shocked by this: the weight of domestic and care work in heterosexual partnerships is overwhelmingly borne by women. This was the case for my own heterosexual marriage, and for most straight married couples I know.

(There are exceptions, sure! I know a small number of men who are the primary parents and housework-doers in their families. And god, now that I’m two sentences into this parenthetical, how interesting to notice what I’m doing here, that I should feel such an urge to equivocate, to clarify that I don’t mean all men, oh no no, not all men…)

I often thought in my first marriage, especially before our daughter was born, that he and I did do a pretty good job of sharing household labor. Looking back, I can see that we did not, but it was good enough at the time. I didn’t believe I could ask for more. It’s not that I ever believed that housework is the province of women. I feel almost certain that he has never believed that either. But we never discussed what we did believe. It never occurred to either of us to have that conversation.

I did not expect to have this story. When we’d first met, as we swapped stories about our families, I was thrilled to learn how progressive his parents were, especially his mother. She’d made a conscious effort to raise him and his sisters without gender stereotypes, giving her children toys for all genders and introducing them equally to sports and ballet and music. I remember the feeling I had upon learning this, the sense that I was lucky, that he was a good man. I loved that he’d been an avid ballet dancer. At the same time, we always spoke of her attempts with a laugh. It seemed a little silly to go to such an effort, like some countercultural experiment. That didn’t mean we didn’t value it or plan to raise our child the same way. We did.

But beyond that, we never talked about who would be responsible for what in our joint life. And because I was socialized as female, taught in ways both subtle and intentional how to care for a home, that a home should be cared for, I became the person in our household who did that caring and the work it demanded. And the longer I did so, the better I did so, the more entrenched our division of labor, however haphazard, became.

In any relationship, there’s always a neater person. It didn’t help that I was the neater one in our marriage. A mess never bothered him, still doesn’t. When I’d point out that he’d left a bunch of drawers open in the kitchen, he’d say he didn’t notice. He just doesn’t see that stuff, he’d say, and I believe him. I believe he didn’t, and doesn’t notice. But when I’d ask for help, for him to try to notice, he threw up his hands. Our standards were different, he pointed out — true, and true of most couples — but more than that, he said, it just wasn’t important to him. This stuff, the maintenance of order and tidiness in our home, wasn’t something he valued. He was occupied with more crucial stuff, he reminded me: he was working hard, running our business. I couldn’t argue with that. He was working hard. I worked too, both for our business and as a writer, but I made less money and worked more irregular hours. I had more time for household work. I valued it more; I had more time; why change a thing? Why was I furious? I couldn’t force him to value the work of running our household.

My point here is also not to bitch about or tell stories on my ex-husband. I find it much more interesting to bitch about what we’re told to value, even the most well-meaning among us, living as we do in a capitalist society governed by patriarchal norms and actual living breathing patriarchs. I mean here to bitch about what my ex-husband had been taught, by dint of growing up in this society, to value as a male person, versus what I was taught to value as a female person. It runs deep.

I remember very clearly the first time I encountered a heterosexual couple who made a conscientious effort to share their household work equally. I remember it not because I thought they were brilliant and wanted to emulate them; I remember it because their system struck me as dogmatic, totally uptight.

I was 22, in my senior year of college. One of my professors mentioned that he and his wife, also a professor, were looking for a student to help them with household tasks a few hours each week on an ongoing basis, paid in cash. I raised my hand. They lived on campus, a short bike ride from my apartment. I’d guess they were in their late fifties, maybe early sixties; their children were grown. On my first day of work, my professor was the one to greet me, to orient me, to show me around their redwood Arts and Crafts home, filled with plants and books and art from their travels. He explained their situation: he and his wife had always split all household and family work equally, and this was very important to them. They’d made a conscious decision to be equal partners, he said, to not default to norms. I remember listening to him say this, nodding, thinking, You weirdo hippies! How rigid, how earnest, how… joyless! He continued: in recent years, his wife had developed a chronic condition that made movement painful, especially fine motor activities. This is where I came in. I was being hired to do her share of the household tasks. I would wash dishes, take out the trash, do light cleaning. I followed him up the stairs to the laundry room, where he demonstrated how they liked their clean clothes folded, from towels to briefs. I scoffed at his exacting instructions, thought it was silly to care so much about such a small domestic task. Especially for a man. I thought, What man cares how his underwear is folded?!

I worked for them for a few months, maybe until graduation. But I never stopped thinking that he and his wife were somehow too committed to their project of equality, too intentional. Surely you could have a marriage based in fairness and not go to such lengths! Still, to this day, I fold my laundry the way he taught me.

Even having had that experience in my professor’s home, or maybe, in a twisted way, because of having had it, it never occurred to me to insist, as a prerequisite for marriage or committed partnership, that we make sure our values on everyday domestic matters aligned. It seems obvious now, writing it out: of course we should have made sure! But pshaw, wasn’t talking about values something only Republican politicians did? Even now, when I try to imagine it — us, newly in love and in our mid-twenties, not yet living in the same city even, sitting down to talk about Big Grown-Up Things like finances, division of labor, child-rearing — I mean, even if we had talked our way through those checkpoints like responsible adults, would we ever have allowed ourselves to envision a future conflict so mundane, so conventional, so depressing, as this? We planned to be equals. But we never actually had a plan. This isn’t what ended our marriage, but it certainly didn’t help it last. Over time, these misalignments accumulated to form a wedge.

And it’s so much more complicated than who is neater or who is messier or blah blah blah. Marriage is a maddeningly complex arrangement of affection, devotion, economic entanglement, emotional support, and dependence. You do not divorce someone because they leave the kitchen messy. I divorced my husband because I could no longer stay married to him — not only because of the ways I was changing as a human being, but because I don’t think, at the end of the day, that our needs and values and lives were well matched, or that we were very good at loving each other.

What I like about Amy Shearn’s New York Times piece isn’t just that it gave me language for my own experience, that it made me feel understood. It’s how beautifully and simply she nails it, the problem and its solution. It’s right there in the piece’s half-jokey title: “A 50/50 Custody Arrangement Could Save Your Marriage.” The solution she proposes is that married parents should try living as though they had a 50/50 custody agreement:

[I]n a well-managed divorce, there is a lot of very tidy and businesslike communication. It’s not perfect, but what is? Divide the tasks and responsibilities evenly, and commit to completing your share without having to be reminded. Give each other guilt-free time away from the family. Alternate who is in charge of making plans for play dates, excursions or chores on the weekend.

Don’t re-litigate it every week. It might feel transactional to chart it all on calendars, but doing so can also be freeing. That’s how my co-parenting schedule works. We are flexible when one of us needs or wants to be, but for the most part, we set it and forget it.

I don’t know if my college professor and his wife would have described their arrangement the way Shearn explains hers, but having spent hours mired in the most intimate details of their home, I have to assume it was something similar. I envy them. It took getting divorced for my ex-husband and I to find a way to live ‘together,’ a way that feels equitable and equal, and it looks like 50/50 custody, achieved with the aid of a dedicated Google calendar, a fair amount of texting, a lot of uncomfortable but necessary conversations, a bunch of mistakes, and, only very occasionally, some screaming.

Divorce is no joke. Nobody wants a divorce: it’s expensive, painful, disruptive, and destabilizing. Our child’s life has been disrupted by our split, and by the back-and-forth of shared custody. There is grief there, emotions and challenges that we will always have to work with. It’s a loss, even when you’re the initiator. But we now spend equal time with our child, and to me, that is worth the heartache. My ex-husband and I now each do our fair share. We each manage our own households, separately, taking care of ourselves and our child. We allocate all shared tasks and responsibilities — paying kid-related bills, making her doctor’s appointments, signing her up for activities — according to our preferences and availability.

Of course, in thinking about all this, I can’t ignore the fact that I am remarried. I straddle multiple experiences: I am a divorced mother, but I am also remarried. I imagine that, until our daughter is no longer physically and financially dependent on her father and me, I will continue to feel acutely aware of my divorced-mother self. But in my current marriage, nearly everything about the way we manage household and family labor differs from my first one. Some of this is, no doubt, because Ash and I have more similar values around family, parenting, and our household. A lot of it, though, is that Ash and I were both raised as girls. We were both raised to be tidy, to pay attention to detail, to seek approval, and to prioritize others, even at our own expense. In my experience, there is a vast difference, both emotionally and practically, in having a partner who was socialized female, versus one who was socialized male.

Or maybe it’s something a little more nuanced — that, though Ash is nonbinary, we still feel that we have a same-sex partnership, a relationship in which there isn’t an ‘other’ gender. Neither of us is ‘the man.’ Neither of us is ‘the woman.’ When it comes to the responsibilities of our home and our family, we tend instinctively to divvy them up based on what we are good at, what we prefer, what we have time for — in other words, according to preference and availability. Let the record show: it feels really, really different to refill the Q-Tip bowl on the bathroom counter not because no one else will ever step up to do it, but because it’s empty and I know my spouse would have done it if they’d seen it first.

I don’t know if I’ll ever get used to how much planning it actually takes to make sure that household and family work is shared fairly. Ash and I have been talking about it a lot lately, as we get ready to have a baby together — which means not only adding a new member to our family, but, for the first time since we met, we will have a child in the house full-time.

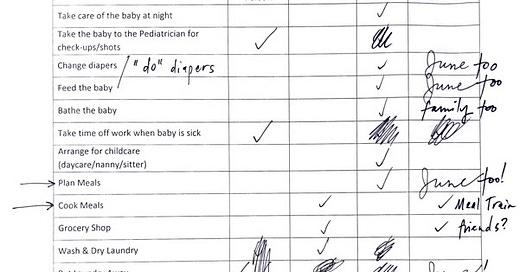

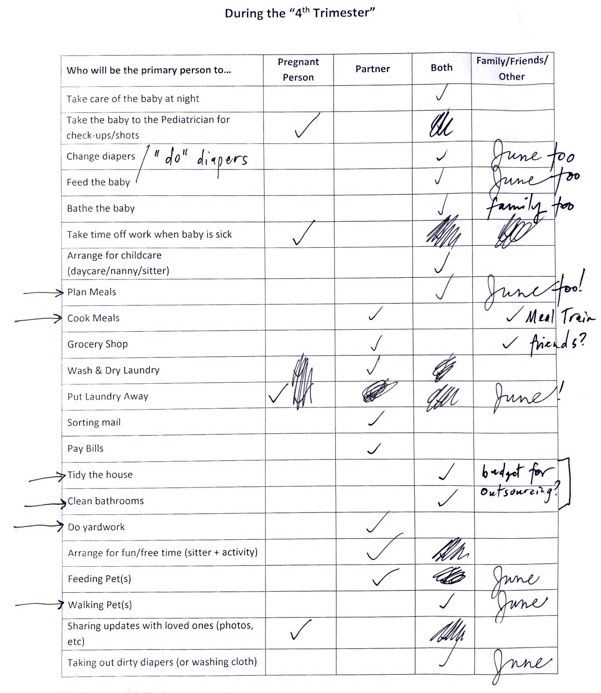

The midwifery practice we’ve chosen offers a sort of education-and-support group for expecting parents, and we’ve been attending meetings. At our most recent one, the facilitator handed out a chart of household responsibilities in the first months post-birth, with blank columns to designate who would be the primary do-er of each task: Pregnant Person, Partner, Both, or Family/Friends/Other. Some tasks were newborn- and infant-related — “take care of the baby at night,” “feed the baby,” “change diapers” — while others were ongoing, like “plan meals,” “cook meals,” “walk pets,” or “take time off work when the baby is sick.” Ash and I leaned together over the sheet of paper, confidently checking “Both” for nearly every task. Of course, we thought, of course we’ll both contribute equally!

Then the facilitator called us to the center of the room, where she’d placed a baby doll and a large bin of colorful plastic balls. One member of the couple was to hold the “baby.” Ash picked up the doll and cradled it like an infant. Then the facilitator began to read down the list of responsibilities on the paper, and for each task, whomever was the designated do-er was to pick up a ball from the bin. A few lines down the page, Ash and I were both already holding a half-dozen balls each.

“Now,” the facilitator announced, “If you’ve been holding the baby, pass it to your partner.” I fumbled to take the doll from Ash, balls spilling everywhere.

We giggled sheepishly, took our seats, and began madly re-allocating tasks. Here is our revised chart, a work in progress:

Checking “Both” was meaningless, it turns out. It’s the equivalent of not making a decision at all. The task will default to someone — unless it is truly a needless task — and if we don’t intentionally allocate responsibilities according to availability and preference, we are setting ourselves up for overwhelm and conflict. The responsibilities chart isn’t so different from making a 50/50 custody arrangement, really. But this time, we’re choosing to actively create the marriage we want, rather than dismantling one we don’t. It is work I hope we’re both always willing to do.

Emphasis mine.

My own math is confusing me, LOLZ. Not sure how much sense this makes?

One of the things I learned from my time in tech was the discipline of the stack-rank: deciding what to do, in what order, with limited time/resources. You rank things ordinally (first, second, third) and do them in that order; obviously the order can change as circumstances and resources change. One of the temptations when ranking (not when doing) was to say "everything is important!" but of course even when true, some things had to be done before others, and the hard work was in getting people to agree on the order in which things would (not) get done. The other temptation was to label things "and a half," "two and a half" etc. when pride or whatever would not allow you to rank a thing lower than another thing. Overcoming those temptations taught me both to be more honest about what things were more important than others and to get more real about the limits of what I could do, and **to talk about those limits.** It was quite clarifying for me.

I think, because of the social conditioning you describe, your professor's rigid arrangement might be the only way to actually have an even divide of responsibilities in a heterosexual couple.

I've been thinking about this a lot because it's the focus of a chapter of Invisible Women, which I've been slowly making my way through - that women do more unpaid labor, even if they're also doing more paid labor than their husbands. My husband and I have the same job, so there's no default of "the man prioritizes career while the woman prioritizes the home." And we definitely do equal amounts of the care work associated with our two young kids.

And he thinks we split the housework evenly. But somehow I spend a lot more time doing things around the house than he does. And sometimes he thinks it's even because I'm doing chores while he's taking care of the kids - but that means he gets low-stress time to focus on the kids while my time with them tends to be interrupted by my other tasks.

In our relationship, a lot of this comes down to cooking. I'm good at it. Once upon a time, I loved doing it. But planning meals, shopping, cooking dinners, packing lunches, and doing more of the kitchen cleaning is a huge workload compared to, say, taking out the trash. But now we're caught in exactly that cycle you describe - I'm better at it so it's more efficient if I keep doing it, but then he never learns to do it and there's no end in sight.