The Barnes & Noble on May Avenue stayed open until 9pm, and sometimes after dinner, my dad would grab his car keys and we’d go peruse the shelves. Toward the back of the store were bins of CDs behind a half-wall that formed a sort of corral, a music store within the bookstore. At intervals among the bins were wobbly kiosks, each with display shelves for a dozen CDs and a pair of ratty communal headphones that dangled from a plexiglass hook. This was a peak time in the history of Barnes & Noble brick-and-mortars: the era of the CD Listening Station.

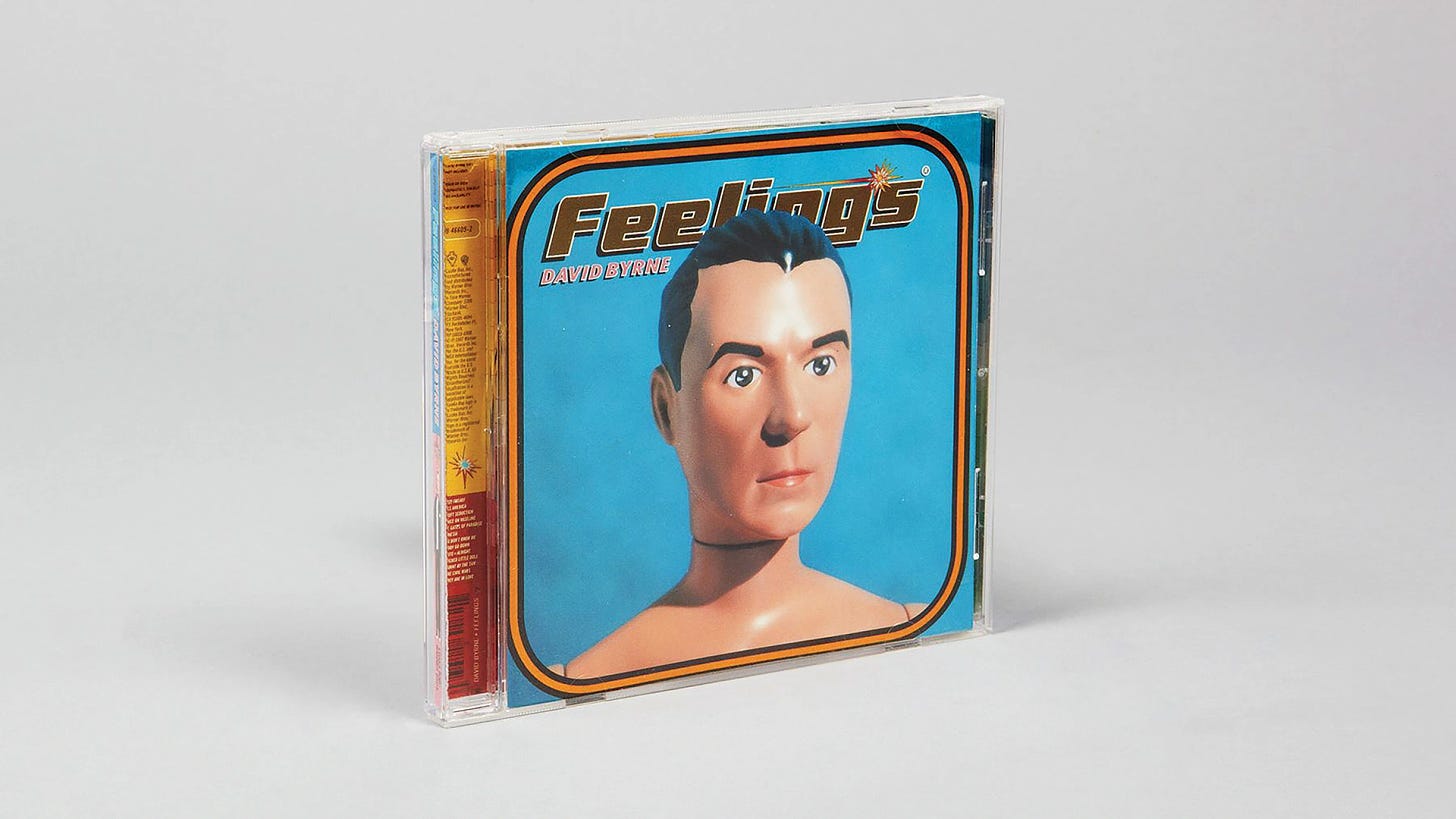

My father was a peripatetic reader, ricocheting from Dylan Thomas to Robertson Davies to fly-fishing narratives with titles playing punnily on the word angling. But while he perused whatever he perused, I’d go straight to the first available listening station, slip on the headphones, and try to find something good. This was where, during the summer of 1997, in the month or two before I left for college, I came upon David Byrne’s solo album Feelings. If you’ve seen the cover art, you’ll remember it. That was what drew me as much as anything: the face of the Ken-like plastic David Byrne doll on that cover, its expression completely unreadable.

I knew the name “David Byrne” from somewhere, though nothing specific came to mind. For the previous five years, I’d been mostly listening to DC hardcore bands that I’d been turned on to by a much older, cooler friend. (I was very proud of what this said about me, because I was otherwise a square.) Feelings sounded nothing like any of that, but I sensed immediately that this stuff was for me. I liked the quality of insistence in David Byrne’s voice, beautiful and strange, and the way it made me want to move my body in angles and twitches. He wrote clever, slantwise lyrics about being a person in the modern world. I would go on to read somewhere that he’d described himself as “an anthropologist from Mars.” Here was a spaceship I wanted to ride.

I took Feelings with me to college in California. My freshman roommates tolerated it, though one complained that “Wicked Little Doll” was creepy, which it is. The summer after freshman year, I stayed on campus to intern in a biology lab, where I spent my days spinning corn DNA in a centrifuge. Through a colleague in the lab I met a girl named Helen, a couple of years older and a David Byrne fan of planetary proportions.

It was Helen who, finally, turned me on to Talking Heads. I loved how, just, weird they were. I mean, I’d known for a long time that I was weird, but my version of it didn’t seem to be desirable. Talking Heads was weird, and people came to them for precisely that. It was the first time I’d thought of weird as something other than a pejorative, seen weirdness as a proclivity that one might not wish away. When I heard David Byrne belt out lyrics like, “I got bad coordination / Stuck a pencil in my eye,” or “Warning sign, warning sign / Look at my hair, I like the design,” I was like, God, WHAT a fuckin’ weirdo! Turn it UP!

When Stop Making Sense was re-released in 1999, Helen and I snatched up tickets to the premiere at the Castro Theatre. Before that night I’d never seen the footage of him dancing with the lamp, and as I watched it there, in that packed theater where the entire audience stood and swayed and the aisles were impassable for all the dancing, I felt something rough in me unhitch and dissolve.

Our seats, it turned out, were four rows behind Jonathan Demme and the band. Everyone whispered; it was notable to see them in one place after years of famous acrimony. After the film, when they climbed onstage to take questions, they stood well apart, as though practicing for a future of social distancing. Helen tried telepathically to ask Byrne to marry her, but it didn’t work. I believe he wore a salmon-colored jacket with feathers.

A couple of years later, on a visit home to Oklahoma City, I got into a conversation with a stranger beside me at the luggage carousel of Will Rogers World Airport. I wondered if he was hitting on me, but he was kind and easy to talk to. He was a porter in the airport, and his name was David (for clarity, and for mystery, let’s call him ‘David H.’). He lived in Chicago, he told me, where he was a drummer. He was in Oklahoma City for an extended visit to care for an ailing parent, and as the months stretched on, he’d taken a job at the airport, which was how he came to wheel an aluminum dolly through baggage claim. We talked drums, about which I pretended to know something. There must have been a real disaster going on with the baggage system, because we stood there long enough to even swap music recommendations. I’m sure I mentioned David Byrne. When my bag finally arrived, David H. asked if we could stay in touch somehow, and I agreed to exchange email addresses. We emailed for a while, and then it petered out.

But the following year, my friend David H. got back in touch. He’d returned to Chicago, he said, and one night after playing in a club, he’d been approached by David Byrne and his producer. They’d watched him play, and they wanted to hire him as the drummer for Byrne’s upcoming tour in support of Look into the Eyeball. They’d play the Fillmore in May, David H. wrote; did I want to come say hi?

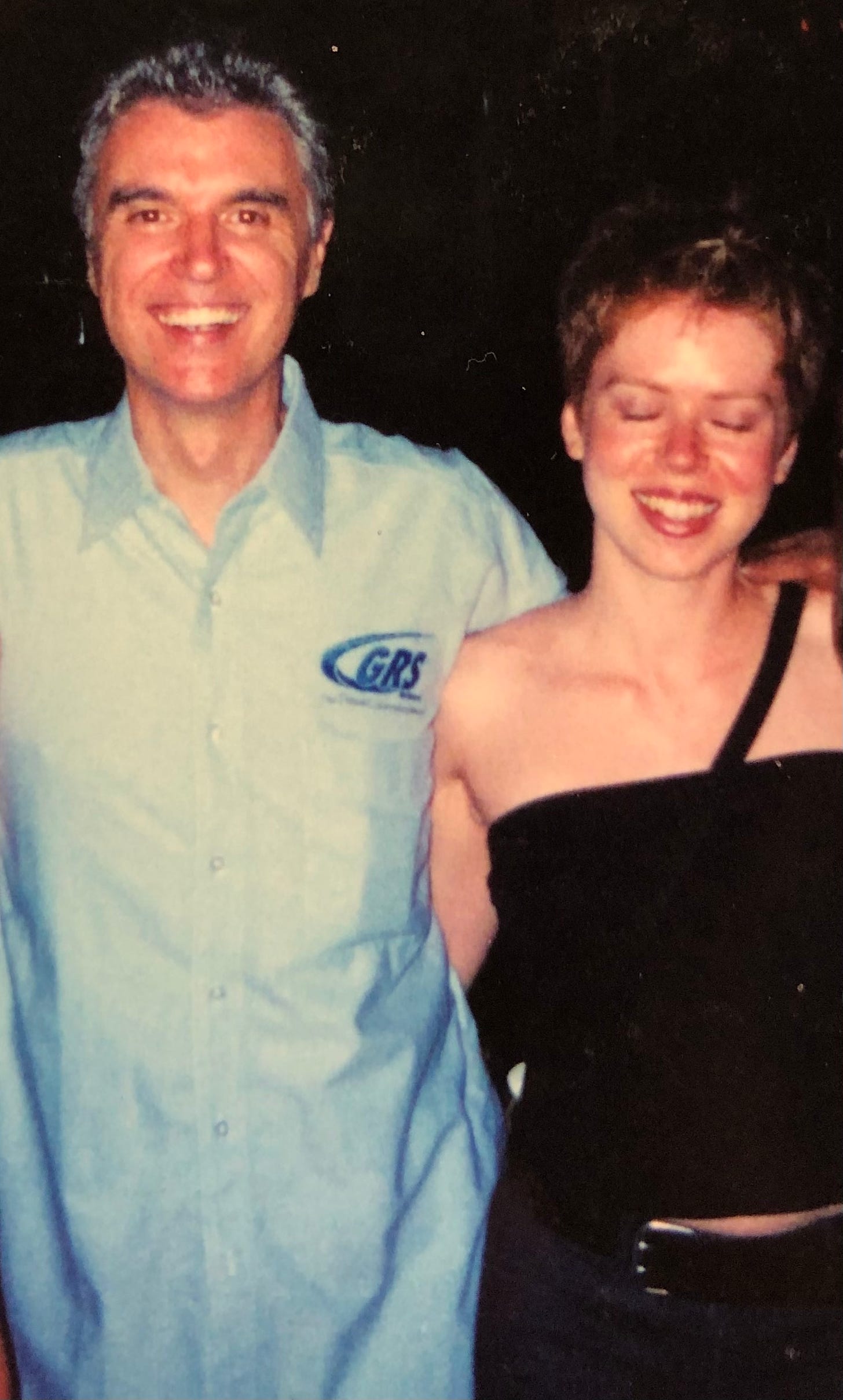

So it came to pass that, on May 31, 2001, I drove up to San Francisco with Helen, my roommate, and my cousin to see my friend David H. play with David Byrne, and to go backstage afterward. I was 22, and I wore lavender eyeshadow and a black tube top. David H. came out to find us after the show and ushered us through an unmarked door. At the end of a short hall stood David Byrne. Small talk suddenly was so, so small. I remember shaking his hand and scrambling, sweating, before settling on a question that no human could possibly answer in any thirty-second exchange: What’s your writing process? I said. My brain went offline the instant I spoke the final syllable; I have no idea what his reply was. Here’s what I look like when I’ve left my body:

After college I moved to France, where I planned to stay for a year. I’d applied for an English-language job through the French Ministry of Education and had been assigned to teach English conversation at a public high school in Saint Cloud, a short train ride from Paris. I had no training and wasn’t given any when I arrived; it was enough, apparently, that I was a native English speaker. I remember showing up to teach in a bubblegum-pink fake-suede A-line mini-skirt with pink faux-fur along the hem. Without actual curriculum materials to use, one day I brought in the CD packaging from Feelings as a visual aid for a lesson. I stood at the front of the classroom and held up the liner notes, on which were printed images of David Byrne dolls with varying facial expressions. I’d choose an image and point to it, and the students had to yell out adjectives to describe whatever emotion the waxy doll’s face seemed to convey.

When that was over, I moved to Seattle. I stayed, and I’ve gone to every show he’s played here since 2002. I always wind up in tears by the end, but then I am a crybaby. I didn’t cry at his “I 🖤 Powerpoint” performance, but I did take a whole page of notes.

My own fandom puzzles me. I don’t have a devotional temperament; I am resistant to the idea of worshiping anyone or anything. It embarrasses me to be a fan. I know he’s just a normal person, that he farts and shits and probably forgets to floss. At points in his career, he’s been known to be a total jerk. I don’t want his autograph – what would I do with it? – and I don’t think about being his friend, though I wouldn’t say no to either if he offered. But I do love this feeling, the way it feels to be a fan – like a crush, like a discovery that never gets less new, like no one in the history of the world has ever felt this way.

Driving my car the other day, with “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On)” playing on the stereo and me attempting the pigeon-bobbing-its-neck thing that Byrne does sometimes when he dances, I had a sudden and morbid thought. If I were to see in the news today that David Byrne had died, I wondered, would the world seem any different to me? Of course I knew the answer. It means something to me that David Byrne is out there in the muck like the rest of us, farting and shitting and probably forgetting to floss, but continuing to make art anyway. And as long as he is – well, I think it must be a kind of evidence, proof of being in love with the world, and that loving the world despite all its malignant nonsense doesn’t make a person soft, or stupid, or naive. It only makes you weird.

P.S. There are a few spots left in my upcoming online writing workshop with LACP! It’s a small-group class — 12 students, max — and will meet on Monday and Thursday mornings from February 28 through March 17. For a full listing of my current workshop offerings (including in-person!), hop on over here.

I grew up in OKC (now living in Washington too) and know that Barnes & Noble well. I suspect we might have shared a pair of those ratty communal headphones.

This was so good that I’m sitting here in tears, M. So, so good. 💙