The Internet is alive with the sound of people talking about their colonoscopies (as the song goes), and I shall hereby express my gladness by joining the chorus.

Last September I turned 45, the age at which routine colon-cancer screenings begin to be covered by medical insurance in the US. I could have done the thing where you just mail in a stool sample, but my doctor said it was a semi-useless test and that she never recommends it, that a colonoscopy is more thorough and reliable. So as soon as my birthday was past, I scheduled one.

The date was set for early December, which gave me two months to get nervous, reassure myself, and get nervous again. I had never been under general anesthesia, and I don’t like needles. I also hate vomiting, and I had heard that many people puke while doing the colonoscopy “prep,” also known as “bowel prep,” shorthand for the combination of semi-fasting and oral medication that, in the hours before a colonoscopy, cleans out your intestines by causing you to defecate relentlessly. Somehow I wasn’t too bothered about the actual procedure, because I’d get to sleep through it. I love to sleep.

As the weeks ticked by, I took tremendous solace in

’s 2022 essay “Welcome to Colonoscopy Land.” The fact that she wrote it — truly a public service. Yes, it’s linked in the opening sentence of this post, but it’s so helpful that I’m pushing it on you twice. Don’t skip the comments!I also received excellent advice from a doctor friend who, because of a family history of colon cancer, has had several colonoscopies. I was bitching to her about the fact that I was going to have to pay $100+ out-of-pocket for the nauseating prep drink prescribed by my gastroenterology clinic. She shared the cheaper and less revolting over-the-counter Dulcolax/Gatorade/Miralax prep regimen that her gastroenterologist and Cleveland Clinic and many others prescribe instead. I was delighted. Of course, because I like to follow rules, I called up my clinic and asked if it was alright for me to go the over-the-counter prep route. They said no, something about how they want their patients to use the prescription prep drink because there’s less room for error? Well. I would not make any errors. I hung up and bought the Gatorade and laxatives. I saved a chunk of money and did not vomit. It was not horrible! At check-in on the morning of the procedure, when they asked if I’d done the prep regime as prescribed, I lied. They were none the wiser. My colon was clean as a whistle, or some other better simile that isn’t coming to mind.

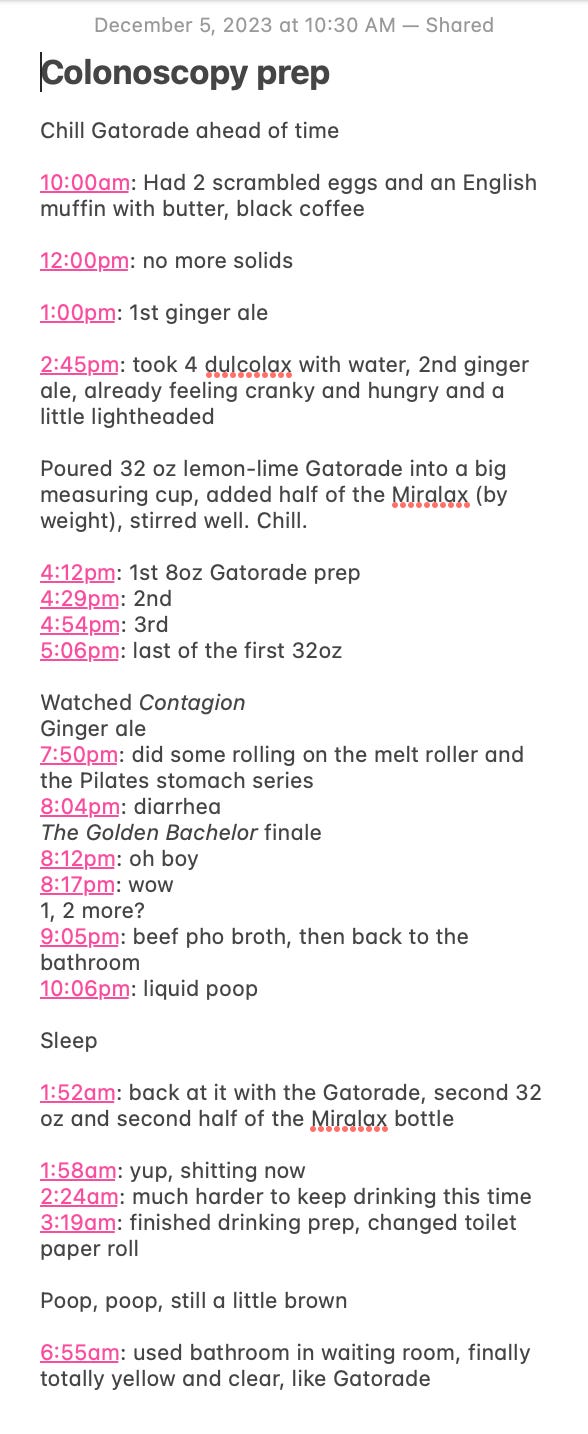

I took notes on my phone throughout the prep process, because in addition to being a rule follower who sometimes ignores rules, let us not forget that I am also A Writer! I do my thinking on paper. I also wanted to remember how it went, for whenever I’d have to do it again.

See? Not a riot, but fine. The colonoscopy itself was a non-event, truly. The propofol sedation was as great as everyone says. I felt normal afterward, normal enough to make cheerful small-talk in the car with my ex-husband (whom I’d asked on very short notice to be my driver after the procedure, because though Ash drove me to the hospital, they forgot to take off work to drive me home, 😑, #ittakesavillage). I’d rescheduled my teaching for the day and asked my mother to be on-call to watch Ames. I could rest. I ate a scone and had a cup of hot coffee. I napped like a corpse. A+, highly recommend all of it.

They found no polyps. Unfortunately, they did find inflammation in my large intestine. The pathology report used a peculiar vocabulary — cryptitis, crypt abscess, crypt architectural distortion — that one might, in another context, reasonably attribute to, I don’t know, cave diving?

After a couple of months of additional non-invasive tests, I was diagnosed this spring with ulcerative colitis. I was surprised, and also not surprised. For the past few years, I’d been aware that I had diarrhea more often than the average person, at least as far as one can get a sense for these things. It didn’t have a real impact on my daily life, but I’d noticed it. I’d discussed it with my primary care doctor, played around with my coffee intake, and reluctantly toyed with limiting certain foods. None of it made a difference, and I’d kind of had a feeling that none of it would. My doctor hadn’t been worried, maybe because I hadn’t been worried.

I was surprised to learn that my symptoms, which I regarded as very mild, constituted ulcerative colitis (UC). I never had any pain or bleeding. I have only twice had a truly urgent shit situation — both times while buying groceries at Fred Meyer, prosaically enough. Who has not had an urgent shit situation in a big-box superstore?

I didn’t know anything about ulcerative colitis, though I have two friends whose lives have been upended by Crohn’s, another chronic inflammatory bowel disease. I would have assumed, had I previously had any reason to think about this, that ulcerative colitis would be more debilitating, more dire, than obvious than my experience of it has been. My doctor was intrigued that I described my symptoms as mild. My inflammation levels remained high, persistently high, over the months between my colonoscopy and diagnosis. But this is, in part, why I’m writing about it: because it was not obvious. It feels like luck to have been diagnosed when my condition is mild, to have it caught and named. Had it remained undetected, unnamed, and untreated, the inflammation in my large intestine would have persisted and likely worsened, causing more severe symptoms — even led to surgery, even cancer.

I am not an expert on UC and can only poorly paraphrase what I’ve been told. No one knows exactly what causes it. The likely causes are genetics and environment, factors like stress and diet. Stress, for instance, could trigger a flare-up of inflammation; then, in someone with UC, the inflammation does not resolve. There’s an autoimmune component, too: a normal gut can heal inflammation and move on, but mine does not. There may also be a correlation with menstrual cycles. The long and short of it is, whatever the cause, you’ve got to find a way to reduce the inflammation, because the risk of colon cancer increases the longer the inflammation is present.

I could monkey around with lifestyle changes, limiting certain pro-inflammatory foods, but because of the degree of sustained inflammation I had, my doctor strongly recommended a drug called mesalamine. Among the drugs used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases — some of which I had seen ads for on TV and have baffling names I have totally made fun of; SKYRIZI, ANYONE? — mesalamine has few severe risks and side-effects. With my current insurance, it costs $15 a month. I am lucky. I take two large mauve pills each night, each the size of an infant’s thumb. It works, no side effects. My inflammation numbers are now close to zero, and wow, hey, turns out I was having a lot of diarrhea, who knew.

Typing this, I imagine that some will read it and wonder why I have not tried a more “natural” course of treatment — for instance, changing my diet before trying medication. There is data to show that certain ways of eating, namely the Mediterranean Diet, can help reduce and prevent inflammation. You may notice, my doctor said, that certain foods cause your gut to flare up. You may find that you feel better if you avoid those foods. But, she told me, you also may not notice any correlation at all between food and your digestion. No one knows what has caused UC in my unique body. The doctor’s overall message was, Take the medication, pay attention, see how you feel.

The doctor did suggest, optionally, a few supplements: turmeric, fish oil, and vitamin D. I take a whole little bowl of pills in the morning and at night. But I was glad, I am glad, that she didn’t press me to eliminate specific foods or eat a specific diet. I have a body that has always been thin, almost certainly because of genetics, but I have spent a lifetime anyway with the voices of diet culture and fatphobia shouting in my ear. At this point, I feel a visceral aversion to anything that implies I should categorize, analyze, restrict, and/or police what I eat, or what others eat.1 I refuse.

But I also think I’d be remiss to imagine that my doctor’s treatment of me — her trust in my reported experience of my body — is unrelated to the fact that I’m a thin white woman who knows how to talk to a doctor. I bet she looked at me and thought, This lady eats just fine. But I wonder what she would have said if I’d had the kind of body we have been taught to mistrust, a fat body or a body of color. It is worth asking. The way we think about bodies reverberates through everything.

There’s more to say, and never enough hours of childcare. Thank you for helping me do this thinking. And if your insurance covers it, schedule your colonoscopy —

M.

I recommend, to infinity, the writings of

(Unshrinking) and (Fat Talk, The Eating Instinct), authors whose work helps me recognize, understand, and dismantle my own fatphobia and choose a freer way of relating to my body and the bodies around me.

I was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis when I was 11 or so. By 13 my entire large intestine was gone and in its place I had a colostomy bag—and nothing has really been the same since ... except that for many of those young and even young-ish years, it was pretty easy and kind of exhilarating to fake it. It's gotten a lot harder. I always want to talk about what I've been through with this condition and all my altered anatomy (to date, a handful of other things have been removed), but I find it so hard. I find it very hard to write about my body at all. Somehow my "mouth" (pen, hands on keys) won't move that way. And it's always so surprising, animating, refreshing, healing, whole-ing, to see someone else so gracefully + stably able to do it. Maybe some day I'll get there. Maybe this is a tiny step. Thank you.

Molly, I really appreciated your commentary on why you went the medication route. I don’t have any personal experience with Crohn’s and UC, but I have a lifelong (I’m roughly the same age as you, I just turned 46) history of severe eczema (and asthma and allergies) that I have tried all my life to manage with diet and supplements. Long story short: it did not work, I suffer from lifelong disordered eating as a result, and it’s actually an autoimmune issue so no amount of elimination diets or supplements is gonna fix it for me. (Not saying that it wouldn’t for other people with eczema/asthma/allergies.) I’ve been on a biweekly biologic injection for a year and it’s amazing. Still working on healing my relationship with food though. That shit takes time.