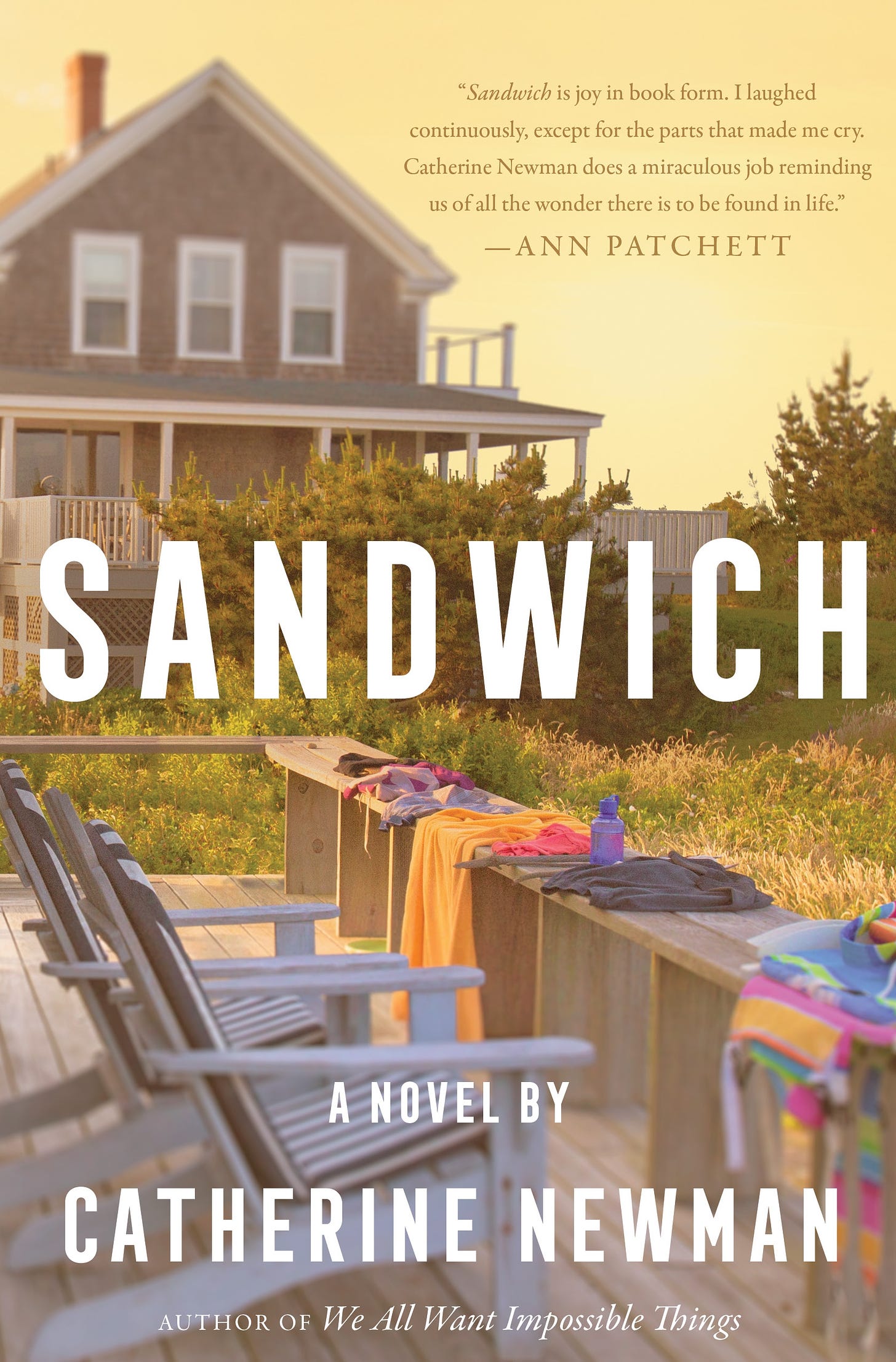

Does need an introduction among this crowd? Surely not. Her new novel Sandwich is out today, and if you haven’t already pre-ordered it, you can regular-order it now.

Catherine is a national treasure. I’ve interviewed her for this newsletter before, and you might be as baffled as I am that somehow it’s been two entire two years since then — and that she’s published two entire books in that span. If you’d like to revisit it, that 2022 conversation makes a good prelude to today’s installment. Here it is:

The conversation that follows took place on May 28, 2024, on Zoom. Sadly I didn’t take any screenshots this time, but we laughed a lot, and so it didn’t look too different from the one above. I hope you’ll enjoy it as much as I did.

The following has been edited by me, and any errors are mine. To Catherine: thank you.

Molly Wizenberg: Number one, congratulations on the Kirkus star. I loved seeing your post about that because it’s one of those things that you only know if you’ve published a book — and the rest of the world is like, What the hell is Kirkus?

Catherine Newman: Thank you for knowing about the Kirkus star. The book got a bad Publishers Weekly review. And, Molly, I feel like you would understand this: I did not read the review! My publicist said, “Oh, this is a shitty review. They assigned it to the very worst person.” And I said, “Okay, I'm not gonna read it.” I don't even know myself! I usually marinate in the bad reviews. I live for the wallowing-around in the muck of how much people hate me and my stuff. But nope! Didn't even read it.

MW: That's incredible.

CN: I am 55 years old — and becoming a grown up this year, it turns out.

MW: Choosing not to self-flagellate! It's a big deal. With my first book, I read every Amazon review and dug myself into a hole of self-annihilation. That was a difficult lesson. So, way to go.

CN: Thank you.

MW: The first thing I want to ask you about is the structure of this novel. It's so clean. It takes place over a week of a family vacation, beginning on a Saturday and ending on a Saturday. How and at what point did you arrive at this structure?

CN: There were two things I wanted to write a book about, and so I wrote a book about both of them. One is the thing that I call reproductive mayhem, by which I mean, in the long reproductive life of a reproductive body, just how many phases there are and how much sort of trauma and scarring there is around having that body, especially a body that has been pregnant a number of times. I also wanted to write about the fact that my family has gone to this one beach house every year for going on twenty-five years, and the experience of the layers and the layers and layers and layers of memories that have accumulated there. Every year that you're there, you're also remembering past years — especially as a parent, that feeling of going to a beach you've been going to since your kid was a baby. There are all these memories that are packed into that place.

CN: I was going to write the book to take place over a number of years – so, for instance, the first chapter would be, like, the year 2000. I was going to pick one day from that summer and write that day, and then I'd write that same day from each year. So chapter one would be maybe July 25, 2000, and then the next chapter would be July 25, 2001. And I just did not . . . [laughs] . . . have the skill to pull that off.

MW: That sounds really hard.

CN: And the funny thing is, the movie I compared it to is this terrible Alan Alda movie from my childhood called Same Time Next Year. He's having an affair with this woman, and they meet on the same day every year for twenty years. They have this one-day-a-year affair. It is the worst movie. It's the most misogynist movie. I mentioned this structure to [my husband] Michael, who had seen that movie with me, and he was like, “Honey, you hate that movie. That’s your only model?” And I was like, “I know! It’s the worst.”

Anyway, I could not do it that way. So I thought I would do it as a condensed week that had a lot of flashbacks in it. I mean, I’m a person who needs a built-in structure. In my last novel, the narrative arc was a person dying and then dead. There it is! It’s built right in. And this was just, like, a week. There’s the structure! It all comes from a profound lack of imagination.

MW: Well, I don't believe that.

CN: Molly, have you written fiction?

MW: I’ve never written fiction.

CN: Ever, ever, still never?

MW: I mean, do we count the stories I wrote as a kid? Like, “The Boneless Hands,” which I wrote in second grade?

CN: I’m so glad I asked. You have to promise me to put in [the newsletter] the title “The Boneless Hands.”

MW: It sounds like, I don’t know, you were going to make chicken cutlets but you came home from the store with the wrong thing.

CN: Damn it. We got the boneless hands.

MW: But I meant to buy breasts!

Anyway, no, I have not written fiction. I think, for a long time, I wondered what the big deal was. Why is fiction the thing everybody aspires to do, the thing that makes you a “real” writer? I question that. But I can also admit that I would like to know what it’s like to build a story that doesn’t rest on me, me as the main character, on me being so transparent, so legible.

CN: Well, I don't know what that's like either. I have now written two novels that don’t do anything other than that. I don’t know. I think there’s fiction where you create a world, and then there’s whatever it is that I’m doing.

MW: Yeah. I do feel certain that I would wind up writing fiction that would map very closely to my own life.

CN: I think you would like doing it. I’m just putting that out there.

MW: I think so too.

But let’s talk about your title. Sandwich. Of course it’s a reference to the sandwich generation, which you and I are both a part of right now. We have children who need us, and we also have aging parents. But then there’s also the other kind of sandwich here. [The narrator] Rocky is a great sandwich maker. Could you talk a bit about how this word works in the novel?

CN: I have young adult children who are sort of three-quarters fledged — a 24-year-old and a 21-year-old. And then I have really old parents — my dad is 93, and my mom’s 88 — but they’re alive and well and very much in our lives and very, very dear to me. So I did want to write about this particular [position]. There have been times in my life when I felt much more called upon to take care of people, but, well — when you’re taking care of little kids, it’s really exhausting, but it’s very obvious that they need you. You can take care of them. I loved that, and I was good at it. I love this too, but it’s so delicate. Adult children still require and also crave a lot of parenting. But the time has come and gone when you can just offer up your opinion about every single thing. You have to figure out how to take care of your grown children in a way that doesn’t oppress them or call into question their sense of competence. On the other hand, you might have aging parents who are totally capable, but they might also require some intervention that’s very subtle. Everyone’s agency is on a platter, but you’re supposed to somehow rearrange it or help serve it, whatever it is. I find that really challenging. I don’t want to overstep. The book is meant to explore this feeling of — all of this is precarious, and none of it is permanent.

MW: And then, of course, you’ve got to make lunch.

CN: Oh right! The other part of the title.

MW: I’m not an inventive sandwich maker. Rocky is. Is there a sandwich in the book that you’re most attached to?

CN: We were just on the Cape over the [Memorial Day] weekend. At the last minute our son, who lives in New York, was like, “I’m going to come camping.” We do two Cape trips: one is the little house in the book, and the other is this camping trip. And our son said, “I’m going to come up on the train to meet you guys and camp.” I cannot even tell you how touching that is. Camping is not really his favorite thing, and he’s had to camp with us 100,000 times. He’s an urban person. But he met us to camp, and so I made the sandwiches that are the sandwiches. It’s tuna salad with mayo, pepperoncini, pepperoncini juice, celery – and it goes into a sandwich with lots of dill, whole fronds of dill in the sandwich. I brought all the stuff to make that for camping because that’s the beach sandwich. You bring a cooler with plenty of ice and it keeps great despite any fear about the mayo.

MW: What kind of bread do you put it on?

CN: Ideally it would be on a baguette, but this was on whole wheat sliced sandwich bread, and it was fine. But I was like, “Eat them as soon as we get there! This thing is not gonna hold its integrity.”

Obviously for Rocky, her love language is making sandwiches. And it’s so my love language too. And the thing I do that drives everyone crazy is just ceaselessly troll for compliments. I need everyone to tell me how good the sandwiches are. You know I volunteer in a hospice. Well, I make dinner in the hospice every Monday night, and then I serve it, and then I go room to room to ask how good it was. I don’t ask how it was. I ask how good it was. Then I sit down in an armchair in case someone has a lot to say about how good the dinner was. I don’t just do stuff altruistically the way other people might. I want to hear about it. [Laughs.]

MW: I want to talk about reproductive mayhem.

CN: But no spoilers!

MW: No spoilers. I just wanted to say that I appreciate your treatment of a very real and painful feeling that is common to every person who has ever menstruated — this sense of being totally exposed, but also completely alone in your body’s experience.

CN: That twinned secrecy and shame and weird exposure and visibility. I’ve had sex with men for a lot of my life, not exclusively, but I’ve been pregnant 100,000 times, and I’ve had every manner of pregnancy ending and pregnancy turning into babies. All of these experiences are simultaneously deeply, deeply — I want to say private, but that’s the wrong word. They’re shamefully secret and also fully exposed.

If you have a miscarriage, you have to tell everybody because you’ve already told them you’re pregnant. But then it’s still kind of a secret because it’s painful, or you feel like a failure, or it’s kind of private because it’s your body, or you feel like it makes people uncomfortable if you talk about it. But all of these weird twinned emotions — they’re universal experiences. I was just reading something where a woman confessed to still sticking a tampon into her sleeve when she goes to the bathroom at work. And I thought, why is that even a thing we do? Why is it a secret thing? As though, if you walked through the office holding a tampon, it’s TMI for everybody?! It’s bizarre.

MW: Ash is a behavioral health provider in a OB-GYN and midwifery clinic, and we talk all the time about how much we would love to watch a cis man go through even half of the physical stuff that a cis woman goes through during her reproductive life. I would relish that.

CN: Michael and I have been together for 35 years. In the Venn diagram of our sexual life together, I’m our whole reproductive situation. He only overlaps in, like, cumming. And parenting. But I’m not talking about him as a parent. I’m talking about the way, if you’re a woman with a uterus in a relationship with a cis man, you literally carry the whole reproductive situation. I’ve had so many infections and emergency situations and pregnancy scares and birth control… things. But Michael has mostly had a consistent bodily experience of himself. We’ve had completely different experiences.

MW: I envy men for that. And then I also feel like, Check this out! I pushed a baby out of my vagina! Poor man, you’ll never ever know…

CN: Right?

MW: Okay, this will be my last question. Rocky recounts this memory of a friend saying to her, “You could decide to be happy. The rest of it? Put it in a little boat in your mind and just push it out to sea.” Rocky is incredulous and thinks she’s being told to repress her emotions. But her friend clarifies: repressing is not the same as setting free.

I love that the friend says this, but it’s very tricky advice. I’ve had people close to me — men — tell me that I could, and should, just decide to be happy. “Why can’t you just be happy, Molly?”

CN: And you want to say, “Because I’m Atlas with the entire world on my shoulders.”

MW: So I want to talk about this idea. How can we live with big emotions and big responsibilities and still find ways to set ourselves free? What does that mean to you? And, God, I’m sorry, that’s a terrible question to have to answer.

CN: It’s a big one.

One thing that’s really surprising me about being the age I am is how much I’m still learning. I hear how corny that sounds. I don’t mean it in a good way — like, oh, I’m still learning and growing so much! Last year, when I was 54 years old, for the first time in my life, I had this new understanding. I was really devastated about some kind of crappy thing, not a catastrophe, but I was really upset. And I thought, You know, I’ll probably feel better tomorrow. And I had never ever thought that before!

And the thing is, it’s true. I have accumulated this bank of experiences that allows me to reach conclusions that help me to get on with things. Maybe I could just . . . let it go? [My daughter] Birdy watched Frozen one time and heard the “Let It Go” song and absorbed it, but I have been struggling literally for decades to let anything go. Specifically things that I feel bad or guilty about or responsible for, things I’ve screwed up or relationships I’ve damaged. There is no limit to how much I can think about them. And I’m just starting to… not.

MW: I absolutely know what you mean. For me, I don’t know if it’s age or if it’s just that my antidepressant is working. But I notice more and more that I have the ability to take a beat. I can think to myself, Hmm, I could intervene. I could get worked up. But I think this is going to blow over. I think somebody else is going to deal with this.

CN: Oh my god, right?

MW: Which is a form of letting it go. Being able to just pause.

CN: It’s life-changing. I have a really good friend who’s a therapist, and I think she’s the character in Sandwich who says the thing about putting it in the boat. I spend a lot of time with her, and she has a lot of good advice. If I’m worked up about something and I say to her, “What do I do?” One thing she likes to say is, “What if you didn’t do anything right now? What if you just let things unfold, and watch? Take a minute to see where it’s headed.” I know I shouldn’t be so mind-blown by that, but I am. It’s hard to let someone else just deal.

I’m on a journey of learning. I say this only to you, because if Michael said this to me, I would actually strangle him. But it turns out that not every single thing in the world needs to be managed by me.

MW: WHOA!

CN: WHOA.

MW: Thank you, Catherine. Thank you for spending this time with me.

CN: I feel like I took up so much time nattering on about whatever. But thank you.

MW: There’s nothing I would have rather been doing this morning. Wait —GILBERT, Gilbert — Catherine, my dog is eating my office rug.

CN: Bye!

I would subscribe to a newsletter of nothing but you & Catherine talking every week!

Molly—I take my hat off to you! You are a brilliant interviewer! And my favourite part was where you included life intervening into your interview in the form of Gilbert eating your carpet! Comedy gold! But I seriously hope it was nothing serious. 😉😀