"My thinking and my drawing, that’s me learning how to be a person"

A conversation with New Yorker cartoonist Liana Finck

Every so often, I get on Zoom with someone whose work and mind I admire, and then I transcribe our conversation, which always takes longer than I think it will, and then I bring it to you. Today that someone is the writer and New Yorker cartoonist .

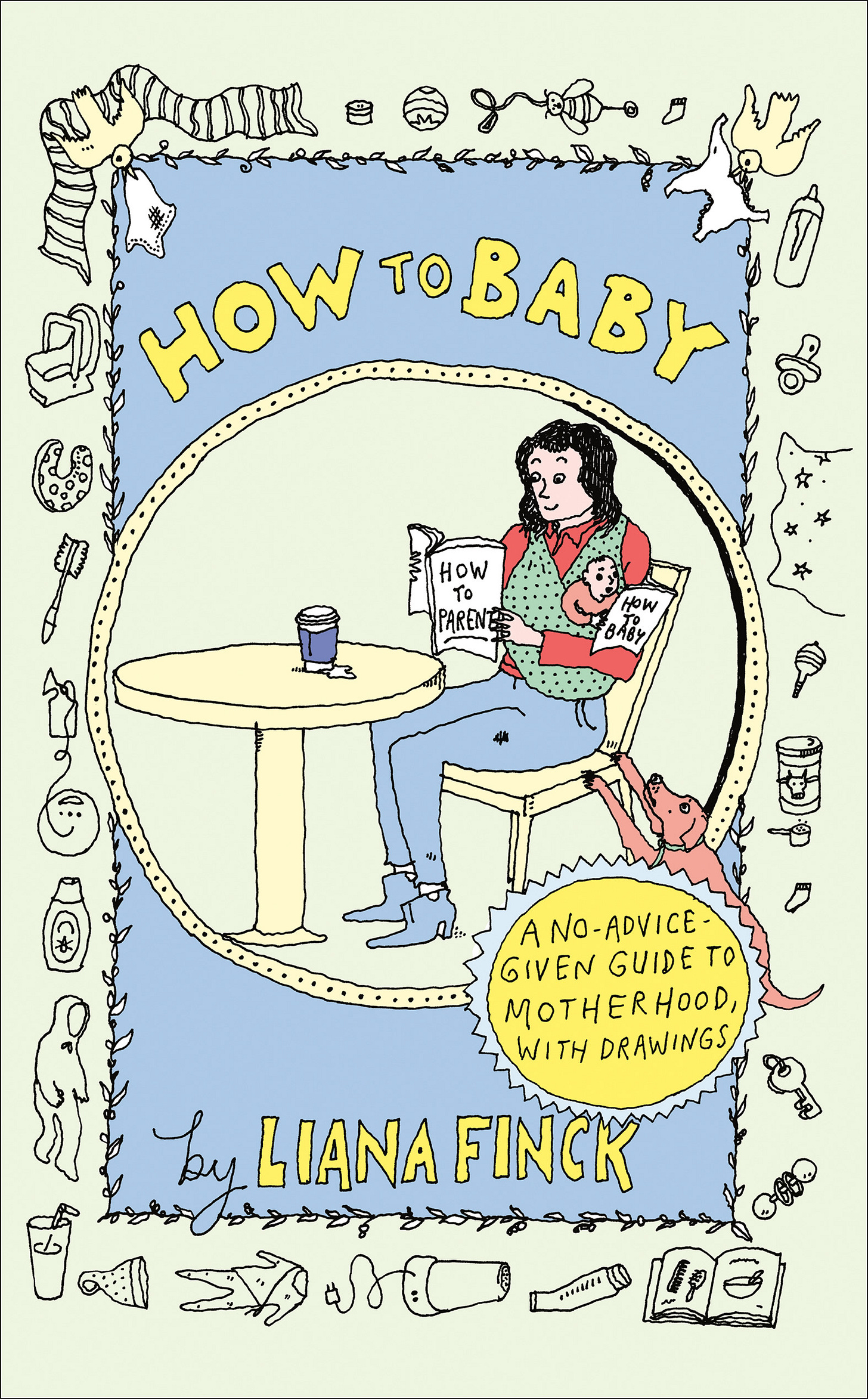

I probably first encountered Liana’s cartoons in the New Yorker, where she’s been a contributor for nearly a decade. But what really lodged her name in my head was her 2018 graphic memoir Passing for Human. Shortly after it was released, I saw it on the Peak Picks shelf at my local library, thumbed through a few pages, and immediately took it home. It was brilliant. Liana’s drawings are weird and wobbly, full of what the New York Times describes as “potato-headed characters” and infused with “a deeply sympathetic contemporary anguish.” Whether exploring the sense of otherness that has dogged her since birth, as she does in Passing for Human, or chronicling the first year of parenting, as she does in her latest book How to Baby, Liana writes and draws with an insight that feels sort of uncanny, as though she were actually spying, in a nice way, on my brain.

Liana Finck is the author of six books, including A Bintel Brief (2014), a graphic novel based on an early 20th-century Yiddish advice column; the graphic memoir Passing for Human; the graphic memoir Let There Be Light: The Real Story of Her Creation (2022), an adaptation of the Genesis story featuring a female God; Excuse Me (2019), a collection of Liana’s cartoons; and the children’s book You Broke It! (2024). She has been the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, and a 2023 Guggenheim Fellowship. She also has, whoaaaaa, a lot of followers on Instagram. You might also know her from her Substack newsletter, which you should subscribe to right now if you like funny and insightful things.

I’ve wanted to talk with her for a long time, but I got up the guts to ask last month, as the pub date for How to Baby approached. I wanted to talk about the book, of course, but also about how she works, about what it’s like to translate ideas into drawings with such precision and sensitivity.

How to Baby comes out on Tuesday, April 30. If you’re in New York, you should go to Books Are Magic this Friday night, April 26, where Liana will be in conversation with Jessica Grose at 7:00pm. (And those of us not in NYC can watch live on YouTube!)

How to Baby is a hybrid project, both a graphic memoir and a parody of “traditional” parenting books. It’s as absorbing as a novel. It made me laugh so hard, I was doubled over and semi-sobbing, and that would have been the case even if I hadn’t been due to get my period the following day. And it’s not only funny; it’s also propelled by a particular fiery rage familiar to most every female person on Earth, especially those in partnership with men. I texted Ash a flurry of snapshots from it, and they’ve since recommended How to Baby to at least a half-dozen of their patients.1

The conversation that follows took place on Zoom on April 8, 2024. It has been edited for clarity and brevity, and any errors are mine. Oh, and Liana’s publisher has generously given me TWO copies of How to Baby TO GIVE AWAY! If you’d like to win one, leave a comment below. I’ll randomly select two of you. Fun fun fun.

Thank you, Liana.

Molly Wizenberg: Okay, I have to begin by telling you how much I loved this thing. Look at all my Post-It flags [holds up copy of How to Baby with 25+ colorful tabs along its edge]. SO MANY Post-It flags.

Liana Finck: Thank you. I hardly remember what’s in the book. I hope it comes back as we talk.

MW: I want to ask first about something I read in the New York Times profile of you, the one that ran in the early pandemic. A couple times in it you mentioned being a person of habit. Assuming that you would still describe yourself that way —I know the world has changed a lot since then — actually, wait, do you still consider yourself a person of habit?

LF: [Laughs.] No. Having a kid makes you unable to prioritize your own habits. I think I am a person of habit, but I’m on hiatus with it.

MW: Is it uncomfortable to be on hiatus?

LF: No — I mean, I’m so busy with what’s in the moment. I think habits are there to protect you from things coming out of left field. But somehow, urgency protects you too. Habits made me able to do my work, though, and I’m doing much less work now, and I do feel sad about that.

MW: I’m someone who has always loved habits, and I’ve struggled with having them interrupted. Especially when I was the [biological] parent of a young child — but also now, with a young baby once again. I’m interested in what you see as the relationship between work habits and creativity. Will you talk about that?

LF: I always feel ashamed about being a person of habit. It’s kind of the opposite of being creative. It’s this need for something very uncreative before you can let loose and be creative. I’m a person who likes to make things and who likes to go off into my own head. I feel very comfortable when I’m able to be very focused and in my head. And at the same time I’m so rigid and so in need of order and so aware of the outside world. Everything needs to be exactly where I put it. I’m sure these needs come from the same weird twist in my brain, but they do seem at odds with each other a lot. I envy people who are happier in chaos.

MW: I do too. It seems like you have a remarkable ability to see life clearly, even when you’re in the midst of it. I’m thinking about your cartoons about stupid everyday human behaviors, or about the routine and repetitive tasks of parenting. You have an ability to look at mundane stuff and make it new for us, make us see it and laugh at it. In the chaos of parenting, has your access to that state of mind changed?

LF: I used to need to process things as they happened, 24/7, by drawing them, and then I would post them on Instagram as soon as I drew them. I still have that need, and I still email myself thoughts all the time. But I don’t have the space or the time or the grace to process things as much as I need to anymore. I feel like I’m pretty busy, like, cleaning boogers and stuff, which is a nice vacation. [Laughs.] And it changes all the time. My kid is going through a really loud, really active phase. He’s two and a half. I don’t feel very well suited to this phase, not the same way that I felt well suited to being immersed in caring for a feeble infant. I didn’t mind letting go of my brain for that. Letting go of my brain to chase someone and wrestle him into pants is a whole different thing. It’s tiring, and I need my alone-time so much more now.

You know, when you said I draw things that we take for granted, or things that we don't usually think about — I don’t take those things for granted. I think it is very hard for me to live. My thinking and my drawing, that’s me actively learning how to be a person.

MW: Hearing you say that — it reminds me of David Byrne. I’ve noticed that before, when I’m reading your work. I’m a huge fan of David Byrne.

LF: Me too!

MW: Then you should take it as a huge compliment! Your work has that same alien-learning-about-Earth quality that his often does.

LF: I think we both have a certain kind of wiring, yeah. I like that he talks about how he probably has a differently-wired brain, but he never really pursued diagnosis. I put myself in that category as well. Art is how I process. Talking about the spectrum — there’s also a spectrum of how people want to define themselves. Some people really want to nail down exactly what they have, and some people are totally oblivious to what they have. I like to be between those two poles.

MW: When you’re making art what comes first: the narrative or the drawing? Or maybe that’s a stupid question…

LF: This is a question that cartoonists talk about all the time, and it’s different for everyone, and it never gets old. It’s also tough to answer, because I think it changes depending on the day. But some people are word people, and some people are picture people. I call myself an idea person. I think in pictures, symbols that are somewhere between a photograph and a sentence. I think of words and pictures as coming from the same place. I think in simplified symbol pictures. It’s all about ideas. It’s not about aesthetics, and it’s not about narrative. It’s somewhere in between words and pictures.

MW: Can you talk a bit about how you found your way to the narrative of How to Baby? These drawings, these ideas — did they come to you in the moment, as you lived it, and then, over time, you figured out how to shape them into a narrative?

LF: Yeah, exactly. I work very differently on every book that I work on. It’s not so much a question of words first or pictures first, but it’s very much a question of narrative first or moments first. This book was the most moments-first narrative I have ever made. I made all of the “moments” in the book in the moment, and I strung them together later in this kind of half-parody, half-memoir — like, a fake how-to-parent narrative. I needed the parody because being earnest makes me embarrassed. I arranged the pictures in order, and I wove the narrative with the pictures. That part was difficult, making a spontaneous-feeling narrative around the pictures.

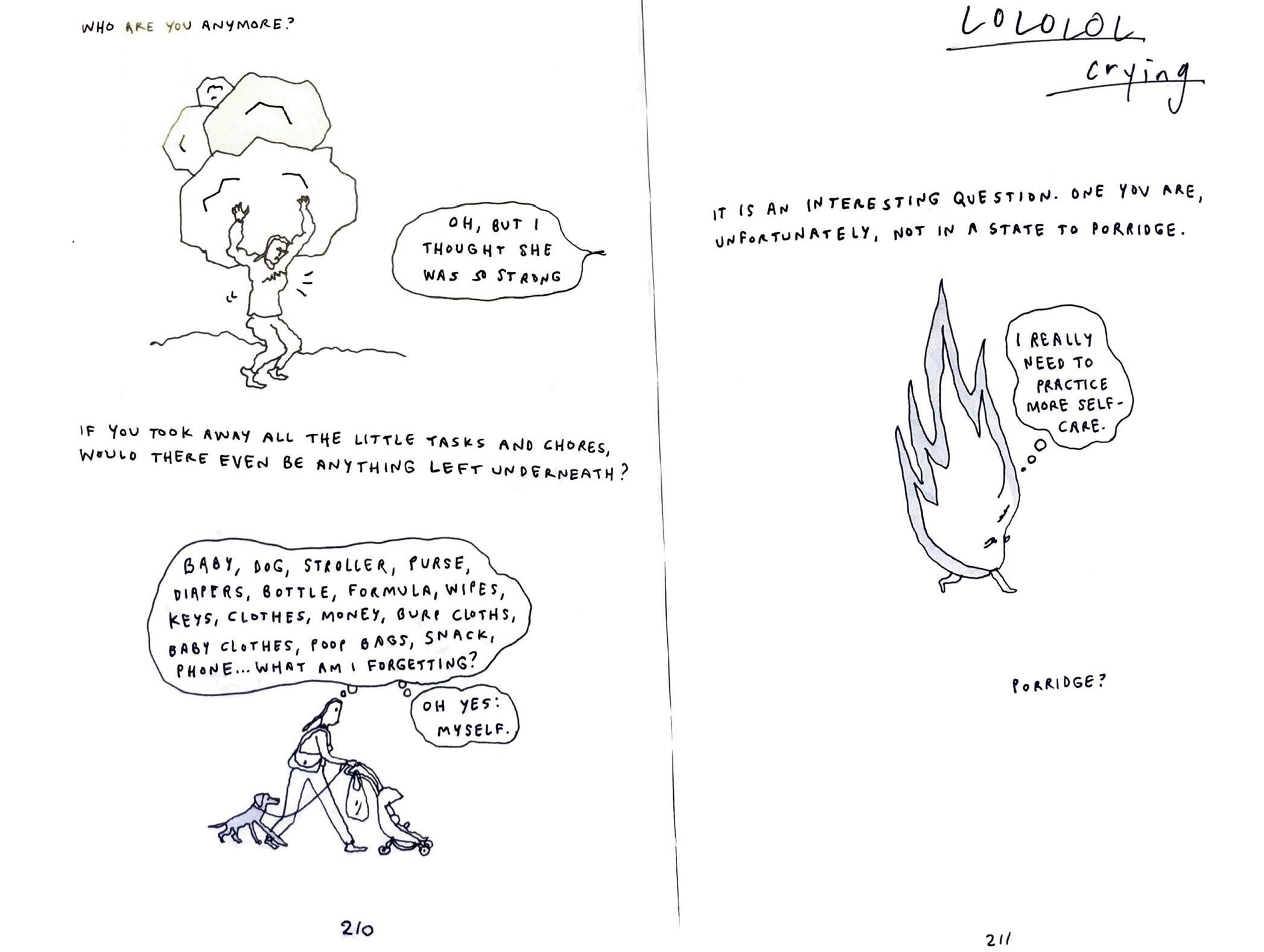

MW: And it worked! It feels seamless, the synthesis of “moments” and narrative. I was right there with you. I mean, look at my margin notes [below, top right]:

LF: I think it’s because I let go a little bit. I think that synthesis is in your brain —which is good. [Both laugh.] I’m very proud that I was able to let go a little. I usually have an iron grip and try to control the reader. Less so, I think, in this book.

MW: You left space for the reader to bring their own intelligence to the effort.

LF: My favorite things to read are loose, but I usually write very tightly.

MW: You said something once, in an interview, about the artist Maira Kalman. You said, “It always felt like she was having a good time doing whatever she wanted. [How to Baby] was the first book where I felt like I could have fun.”

LF: I adore Maira Kalman. I think that’s what I mean by looseness. I think she has a real trust in her readers and viewers, and she lets herself really play. Like, she’s not agonizing over, Oh my gosh, will people understand what I’m trying to say? She has a talent for joy. And she also works at it and does it very well. I think the looseness I’m describing is about being playful and not striving for understanding so intensively that it becomes, like, an academic thesis or something.

MW: What enabled you to be looser with this book?

LF: Parody, I think. I find parody really, really fun and an end in itself. With other types of work, I get very serious. It’s like I plunge into a really deep hole. With parody, I know when I’m done.

MW: I loved seeing Roz Chast’s name in the Acknowledgments. I love her work. What does she mean to you?

LF: She’s very much my favorite artist, but besides that, she’s my friend. And I feel weird about this word, but I would also call her my mentor, because she’s a generation older than me and she is very good at what she does, and she’s very generous in talking with me about work.

And she just so clearly loves having children. I don’t think I’ve encountered a whole lot of that [sentiment] in people who are very successful. Maybe it’s there, but people don’t talk about it so much. Having a woman in my field whose work I love so much and who I’m friends with never say a bad thing about being a parent was so unusual for me. I’ve taken in so much media about parenthood, and I know so many parents, and it always seems really, really hard. Before I decided to have a kid, I was really divided about it. She’s a big part of why I decided to do it.

MW: This book captures so beautifully the brutality and also the incredible thrumming love of the first year. It’s tricky to write about the profound life-changing love one has for one’s kids and make it something new, not have it be saccharine or one-dimensional —

LF: It’s so hard.

MW: But you did it, maybe because there was also this broader goal which was parody. The book also has a lot of — I don’t want to put words to it, but I also loved how much anger there is, about gender dynamics in early parenting and the strain of having a tiny baby. You resist oversimplifying it.

LF: While I was writing the book, I was really in the depths of anger at partnership —man-woman partnership — and the patriarchy. In retrospect, I think things were really heightened because of hormones. I was also in a pretty new relationship and a brand new marriage, and we did everything really fast.

It’s gotten way better since then. Oh man. I’ve come to understand that my now-husband thrives in chaos, and I thrive in order. It’s enabled me to ask for more, funnily enough. It’s enabled me to see things as they are and to ask for help outside of our marriage. More babysitting, things like that. It doesn’t hurt that our kid is older now. Though right now he’s very difficult. He was up all night — apparently that’s a toddler thing?

MW: Oh god, I’m so sorry.

LF: Is it a toddler thing, do you remember?

MW: I don’t remember. There’s so much I don’t remember. Lately, because our daughter June is watching us parent this baby who is ten years younger than her, she’s always asking, “Mama, did I do X, like Ames does?” Or, “Mama, when I was little, did you do X thing with me, too?” “Did I cry too when you changed my diaper?” And I know I could just say yes, or whatever. But the truth is, I do not remember.

LF: Because you were busy taking care of her. You weren’t making memories.

MW: Meanwhile, my kid cannot fathom how I have forgotten so many pivotal moments in her personal history.

LF: She’s becoming — she’s learning nostalgia.

MW: I love that you would say that. That makes a lot of sense to me. I’m a very nostalgic person. I think it’s why I’m a memoirist, actually. I feel nostalgia very physically. Like an ache, a good ache. I love the feeling of nostalgia.

LF: I’ve never heard someone say they love it before! I love hearing that. Hmm. I don’t feel nostalgia a lot, but I really welcome it. I feel it at crucial moments, like when my parents moved out of my teenage house, or when I move. It often takes the form of vivid dreams.

MW: I wish it took the form of dreams for me.

LF: I always dream. Often I dream about places. I see them in dreams. During the pandemic, I would revisit the same few places, and there was this feeling of intense longing for them. I could never stay there long enough.

I have trouble bringing memories forward into work, though. I’m so curious about how people do that. I feel this discomfort with getting things wrong. It’s easier to feel nostalgia in dreams. Then you just feel the presence and you’re not worried about getting it right.

MW: I think what makes writing from memories hard for me sometimes is trying to find the right words. I’m not trying to get every detail of the memory right, but I’m trying to find the words that make as close a match as I can to the feeling of the memory.

LF: How do you find them? How do you judge if the words are right?

MW: I think it’s a sensibility a writer or artist has to sort of cultivate over time. The ability to know when your work feels right to you.2

LF: I have trouble with it. I write crap and then I edit it a lot.

MW: I have a hard time letting myself write crap. I do a lot of writing in my head, just staring out the window until I find the right word.

But speaking of feeling, you do a beautiful job of illustrating feelings. How did you learn, or what are some things you’ve done to try to get better at drawing a feeling?

LF: I've always felt strongly, and I used to have trouble expressing what I was feeling. And I also felt very ashamed to have feelings that often seemed to be about the wrong things or were too intense. If I need therapy about anything, it’s my terror of planning, or canceling. It’s the most neurotic I am. They’re feelings that, like, would be better had about life-or-death scenarios. I started letting them out in my twenties by drawing them, and it was really helpful for my mental health — and also for my drawing.

MW: Have you done therapy?

LF: I’m in therapy now for the first time, for the first successful time. I started right before I gave birth because I was so worried, honestly, about how to parent with another person. My therapist turned out to be my next-door neighbor, so we do therapy walks. She’s an opera director, and she understands the world in a very specific way that I don’t. I’ve really shifted. I was worried that I would shift into someone who didn’t make the same kind of art — and I was right, I have shifted into someone who doesn’t make the same kind of art, and who is much less angry. But then I also parented in this pandemic. It was all part of the same wave that shifted me into a more introspective, quieter person, which is what I used to be before I got angry in the first place. So it’s probably for the best.

MW: Thank you for sharing that. I want to know what you’ve been reading lately, or what you read while you were working on How to Baby.

LF: I was deep in a self-help reading phase, so it came naturally to parody all the parenting books I was reading. There were some that I loved, and some that I loved making fun of. I love to make fun of What to Expect. And that Harvey Karp book about the fourth trimester.

MW: The Happiest Baby on the Block! Totally. That didn’t need to be a whole book. It could have been a pamphlet.

LF: A paragraph.

MW: Did you have a Snoo?

LF: No, but I did consider it.

MW: Us too.

LF: Is Ames in a crib yet?

MW: Yeah, he’s been in a crib in his own room since he was like ten weeks old. First he was in a bassinet in our room, and then in our closet. He was like the Infecteds on that show The Last of Us — he made these crazy clicking and snorting sounds all night long. It was alternately really cute and extremely annoying.

LF: We’re back to having a kid in our room. He won’t stay in his bed. I really regret not getting a king-size bed.

MW: What’s your childcare situation right now?

LF: I don’t have enough. Last year I was in Berlin alone with my son for four months [on a fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin]. I had eight hours of daycare a day, but it took an hour to get there and an hour to get back. So I had six hours to work. Before that, the first year, my parents helped out twelve hours a week, and my husband was unemployed, so we were splitting the load most of the time. But after he got a job, well, it was a really intense job and an intense transition. We had, I think, six hours of childcare a day, and I was doing everything else. It’s sort of happened in waves. Now my son is in full-time care, and we’re supposed to pick him up at like five or six, but he’s been having a hard time, so we pick him up earlier. That means I’m back to six or so hours a day. It’s not enough. Are you doing a lot of parenting right now?

MW: I am. We have 24 or 25 hours of childcare a week, which is what we can afford. My spouse works a job-job, forty hours a week, outside the house, and my work is more flexible, so I wind up filling in the hours before or after childcare. My mother also helps a lot, maybe six hours a week.

LF: Are you and your partner good at sharing the work?

MW: We are. And the fact that we are makes me notice and realize how accustomed I became [in my heterosexual marriage] to just taking on the work, even when my significant other is fully capable of doing it. I still have this urge to take on everything, to take care of everyone. And Ash sees it, sees the work I do, in a way that my ex didn’t. It’s been amazing to be able to talk about that with Ash — and also very difficult, trying to undo my habits.

LF: My husband won’t do something unless I tell him to do it. So I not only have to stop myself from doing it, but I have to tell him to do it. We’re wired so differently.

MW: Ash is nonbinary but was assigned female at birth and raised as a female, and even though there is a lot of stereotypically female-designated domestic labor that they just never learned or cared about — like cooking; I’m the one who cooks — Ash still has this baseline socialization toward being attentive. Attentive to domestic details, attentive to our home. Interested in how our home feels. And that’s wonderful, and it also makes me despair for, like, how did things get this way between men and women? My life is so different in this marriage, labor-wise. I forget how hard it really was when I was not only the one feeding the baby with my own body but also, like, forever thinking about the baby, our home, the garbage collection schedule, whatever. What I have now feels literally unbelievable to me sometimes. I may parent more during the day, while Ash is at work, but when Ash gets home, I’m like, Here’s the baby! He’s all yours! And it’s not like they’re doing me a favor. It’s, like, of course.

LF: My head’s exploding. Don’t they need to rest after work before they go back to work for the next 14 hours? Not just Ash, but all partners?

MW: That was the kind of privilege I gave my ex, when our daughter was a baby. My thinking was, he and I owned a restaurant together, and he was the chef, and we were both financially dependent upon that restaurant. And when June was tiny, I wasn’t working much. So I felt incredibly protective of his health and his sleep and his stamina, because I needed him to run the restaurant and run it well. And at the same time, I was furious at the whole situation.

LF: I want to say, as a self-employed artist who does make a living and who was the only employed partner for a long stretch, the money thing is a red herring. I’m so curious to talk to a group of women artists versus women with “day jobs,” to see if the problems are different [vis-a-vis their male partners and parenting]. It’s hard to be the one with the flexible schedule.

MW: And my work is mostly invisible. I don’t even have outlines lying around. It looks like nothing from the outside.

LF: When you said you look out the window — I’m so afraid to look out the window because I feel like a part of me would be, like, You’re not working!

MW: One thing that’s been vital to me about [my current] relationship is, it’s the first relationship in which I truly feel and believe that my time is respected by my partner. They are not watching or judging the way I use my time. I don’t know what to attribute that to, other than the fact that Ash is a good person and they trust me and they understand at a deep level — more readily than I do, I think — that my work is at the core of who I am. That understanding is something I never knew I could have, or that I deserved. Anyway, nobody uses their time “well” all the time, do they?!

LF: You need in-between time, desperately, in order to make anything.

MW: Speaking of time, I don’t want to take up any more of yours, Liana. But I so admire your brain. Thank you for having this conversation with me.

(Pssst, don’t forget: if you’d like to win a copy of How to Baby, leave a comment below.)

Ash is a behavioral health provider in an OB/Gyn and midwifery clinic; I may not have mentioned that?

This is not my original idea! I first heard it articulated by the novelist Garth Greenwell.

I loved reading this. I am the sole breadwinner in my little (not so little? we have four kids) family and my husband is a stay at home dad. My job is extremely demanding and stressful; despite that, for all these years I was solely responsible for the meal planning/cooking/scheduling/food shopping/night feeding/nursing etc etc. It felt all the more heartbreaking because everyone around me was constantly clutching their pearls at how LUCKY I was to have this unicorn husband who, gasp!, spent time at home with his kids! My resentment, exhaustion and just outright fury was all internalized and felt like ungratefulness in the light of how others viewed my life and partnership with my husband. It's only been in the past 1.5 years, after we had our final baby, that my husband has started to really see the inequity and has made a huge effort to right the ship. As amazing as that has been, I often wonder if the gaping wound the first 7 years of motherhood created in our marriage is something we ultimately will be unable to overcome. I suppose only time, and a hefty dose of forgiveness, will tell.

Great interview, Molly. I always learn something new through your interview series.