I’ve always loved to read letters, especially if they aren’t meant for me. I see this not as a temptation to mail theft, but a condition of being human. I mean, if I were the only one drawn to reading other people’s mail, we wouldn’t have The Jolly Postman, for one thing, or the Griffin and Sabine books. Remember those? My mother kept her copy of Griffin and Sabine on the shelf in her bedroom, which gave it the mysterious appeal of something off-limits. I decided not to ask for permission and instead read it on the sly, carefully slipping each letter out of its envelope and then carefully replacing it. This covert operation was fitting, it turned out; the experience of reading a book of letters itself can feel a little sneaky, delicious-sneaky, like eavesdropping. If reading a ‘regular’ novel is like eating a slice of cake, an epistolary novel is like a bag of Skittles – the format bite-sized, the good stuff meted out in discrete packages that make you want more more more1.

For my 18th birthday, I asked for The Habit of Being: The Letters of Flannery O’Connor. We’d read Wise Blood in junior-year English, so I was now a reader of Literature, and the author’s correspondence was a logical next step. O’Connor2 was funny, contrary, and I understood maaaaybe fifteen percent. This bag of Skittles was for MFA students. But that epistolary thrill! Reading O’Connor’s letters gave me the shivery sense that the author was close by, that she was somehow within earshot, that she was reaching out toward… someone who was not me… but our shoulders might graze in passing.

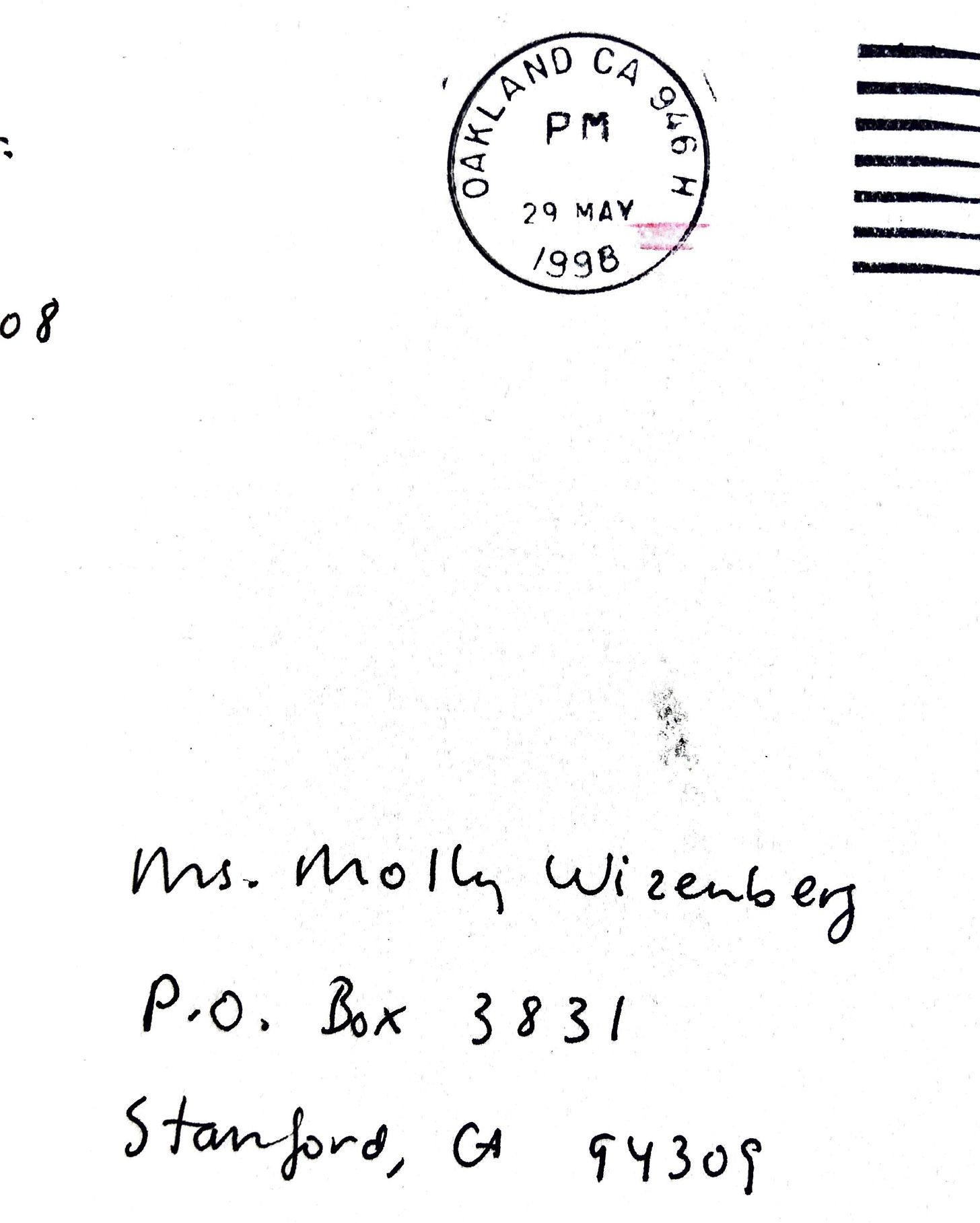

Maybe that thrill is what it is because I don’t get a lot of letter-letters. Like most people alive today, I get plenty of email but little actual mail, and even less that comes in a hand-addressed envelope. A real letter is special. The ones I get, I tend to keep, a habit I’ve had since my cousins and I were teenage pen-pals. It didn’t surprise me last month to find, in a storage bin in the garage, an envelope addressed to my college P.O. box. But the handwriting on it did give me a jolt. I dropped to my knees and grabbed the envelope with both hands. I hadn’t seen it for maybe close to a decade, long enough to forget I had it. It was a letter from Mollie Katzen.

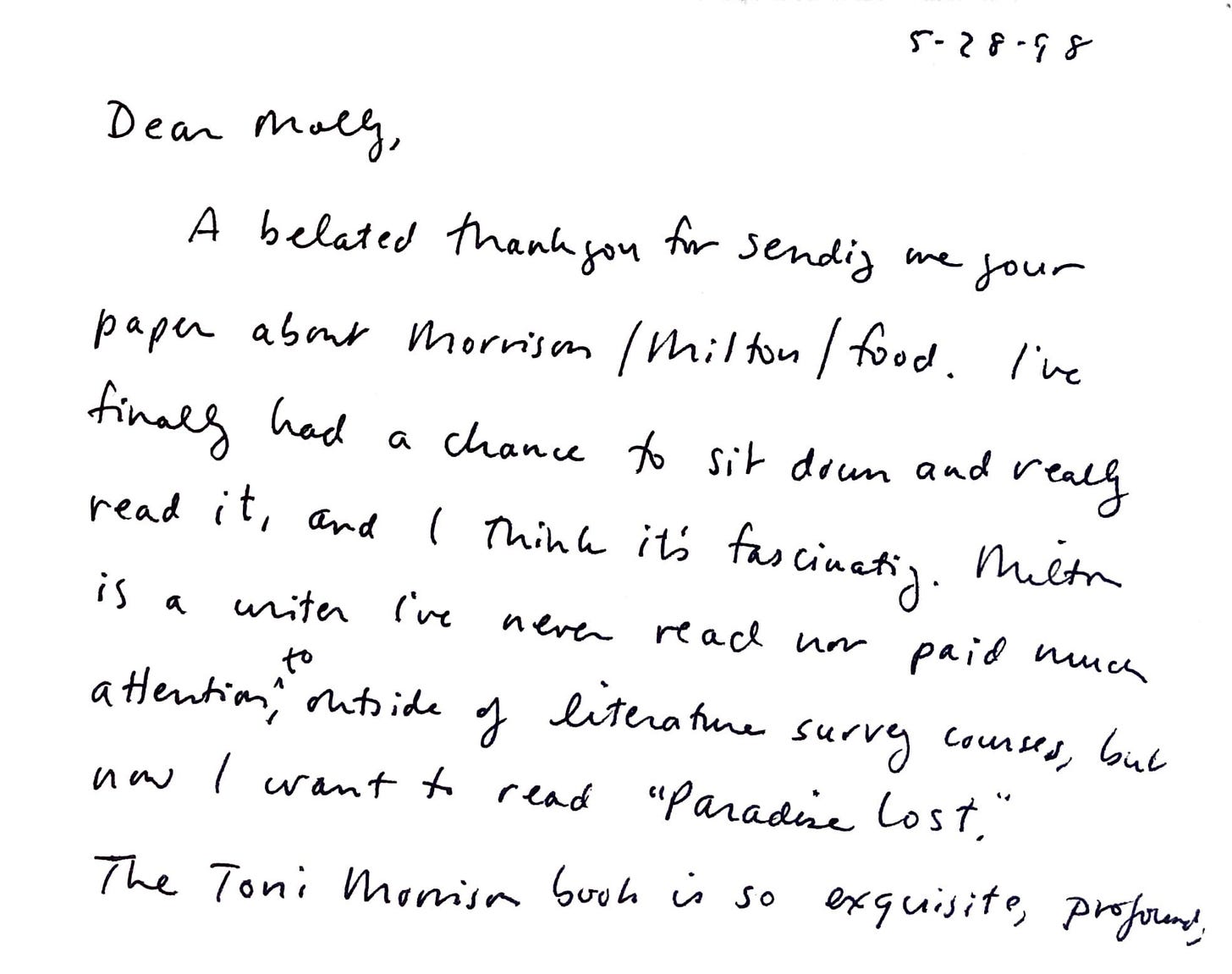

I bet you know this handwriting, too, at least if you’ve been a vegetarian in the United States anytime since 1977. I was a vegetarian from 1994 to 2003, from age 16 to 25ish. But I’m sure my parents owned one of Mollie Katzen’s cookbooks even before I gave up meat, because everyone had a Mollie Katzen cookbook. Her work, starting with the classic Moosewood Cookbook in 1977, brought vegetable-centric cooking to a mainstream audience — made it approachable, inviting, delicious, a pleasure. Even if you somehow don’t think you know her work, you do. You’ve eaten her food, I guarantee it. I bet you’ve seen her illustrations and art, too, and the hand-lettering that set the tone of her early books. I remember thumbing through The Enchanted Broccoli Forest as a teenager newly interested in cooking, and that round, half-cursive lettering felt to me like a hand extending itself through the page. One of the earliest meals I cooked with my mother — cooking with; not just helping — was Autumn Vegetable Soup from the Still Life with Menu Cookbook, my favorite book from the Katzen oeuvre. Chopping Swiss chard for that soup, I was in awe of the hot-pink stems. I remember watching the cubed butternut squash turn the broth orange, as though Katzen’s work made me see art everywhere.

In the fall of 1997, when I was a 19-year-old college freshman, I went with my aunt Tina to a San Francisco bookstore event for her then-newest book Mollie Katzen’s Vegetable Heaven. As you know, I am not a natural at talking to celebrities, and Katzen was a celebrity to me. It was not enough to thank her as she signed my book, or to tell her that I loved her cookbooks and that my family cooked from them all the time. I also felt compelled to tell her about a food-related paper that I had been writing for my first-quarter-freshman-year humanities survey course. And then I mailed the paper to her. And though she was on a massive book tour — 26 cities, the Internet tells me — she took the time to read and digest it, and then she wrote a thoughtful letter in reply.

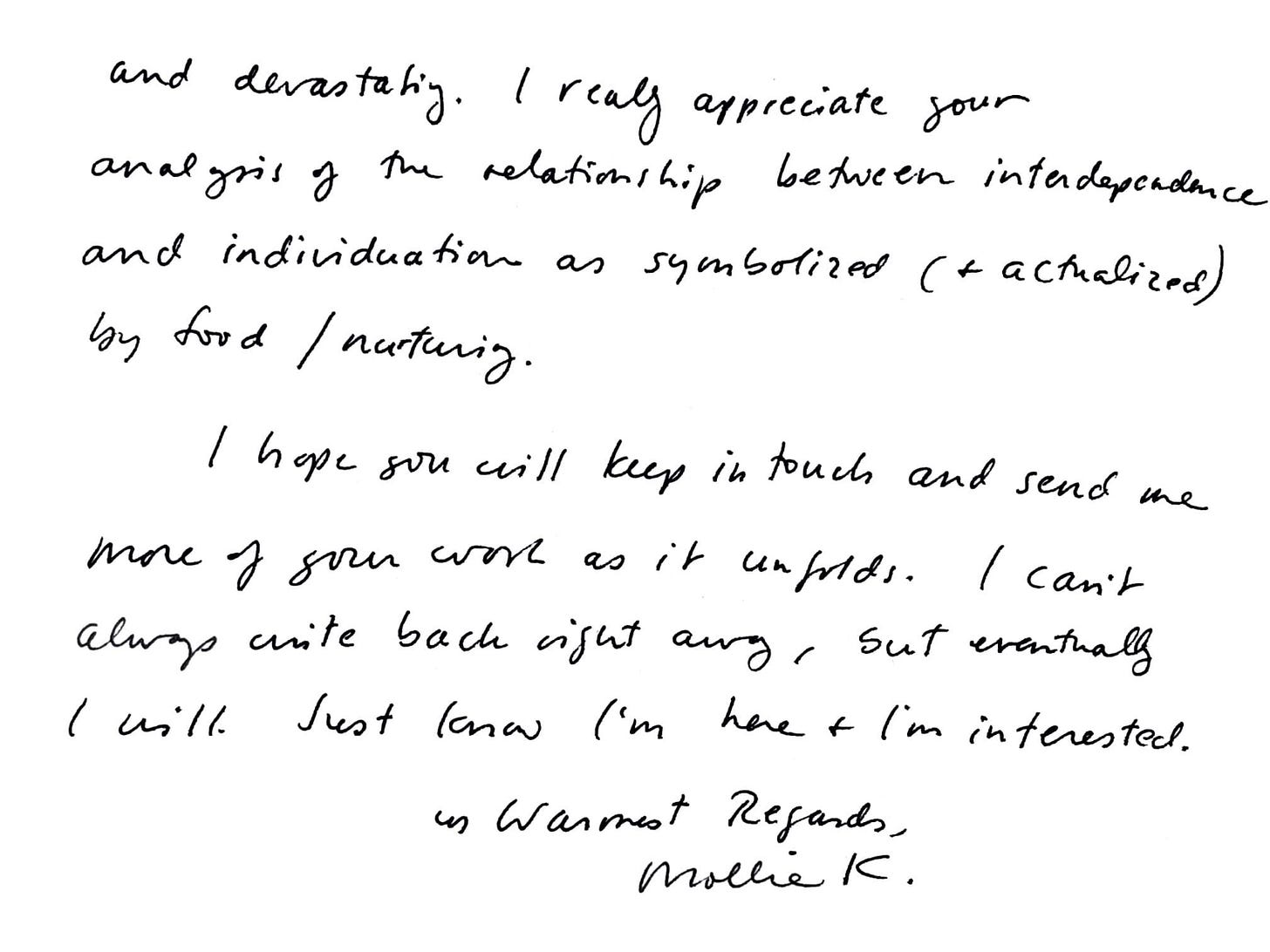

It’s been 24 years since this correspondence, and I’ve forgotten and re-found it many times. Each time I’m at first flattened by embarrassment: I’d sent her my goddamned college homework. Then I’m struck even flatter by Katzen’s reply — the presence in it, the generosity, the warmth and consideration she offered.

This time, as I kneeled there in the garage, I had a new thought after those first two. It felt as though I were reading a letter written to someone else. If a quarter-century means anything, I was. This was someone else’s mail. Let’s call her Our Molly. God, is she sweet or what? She doesn’t want to be; she wants to be interesting. But sweet is what she is, and so, so earnest. Our Molly admires Mollie Katzen. It’s natural that she should want to share her writing, which was and is her art, with one of her heroes. And her hero has the grace to receive it, to even extend her hand for more. I’m here + I’m interested.

Literally nothing could be better. Our Molly cannot reply; it would be a string of stammers. She shoves the letter in the drawer of her particleboard dorm-room desk and then eventually into a plastic box, which finds its way to a garage in Seattle. Now it belongs to everyone.

For an ongoing supply, try the Letters of Note Newsletter by Shaun Usher. Pure gold.

No mention of O’Connor should be without an acknowledgement and discussion of the racism in her work. This is a good and important read.

Molly, this means so much to me. And the admiration is completely mutual. I still have our correspondence, all these years later. xo

Molly, I just want to say that the magic Mollie Katzen held for you is the very same magic you have always held for me. When I stumbled upon A Homemade Life in Powell's books when I was 13, it was like a whole other world suddenly opened up. YOU made that happen for me. I hung on to every word of the book, every word of Orangette (yes, I actually went through the archives in their entirety), and slowly but surely, you taught me how to cook. We've met in person twice, once at Delancey when I was maybe 14 (and quite literally begged my aunt to drive me to Ballard from Issaquah just to eat there) and once at Powell's when Delancey the book actually came out. Both times I felt absolutely starstruck and I have no idea what I said but I do know that you were incredibly kind and encouraging, and you held the exact same type of welcome warmth for me as you write about today. Hope you know you're a hero to many.